Get weekly tips, recipes, and my Herbal Jumpstart e-course! Sign up for free today.

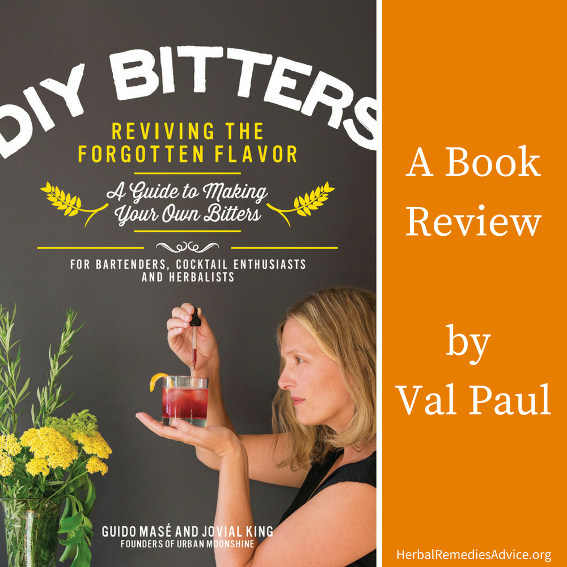

DIY Bitters: Reviving the Forgotten Flavor - Book Review

Share this! |

|

Why Bitters?

The introduction of DIY Bitters: Reviving the Forgotten Flavor opens by asking “Why Bitters?” It’s a good question. We hear about bitters as they relate to cocktails or you may have heard your favorite herbalist(s) also discuss bitters. But is it a taste that we really want more of in our daily diet even if we know that it’s beneficial? Authors and herbalists Guido Masé and Jovial King show us how this unpopular flavor benefits our health, how growing and/or using bitters can be an ecological act, and how it can be truly enjoyed as a part of our daily lives.

Taste

Taste is a subject that I am passionate about and I thoroughly enjoyed Masé and King’s writing on the subject. The first chapter explores the flavors in bitters: taste, aroma, and mouthfeel. Five taste receptors are discussed, four of which will be familiar to those who know the tastes in traditional herbalism and a fifth that isn’t included in those models. Their take on the bitter taste is fascinating, as they have five different categories of bitter. The sections on aroma and mouthfeel are also familiar yet still unique. This chapter is engaging, practical, and offers a lot of insight on the tastes whether or not you have any experience studying them.

Chemistry

In the second chapter, we learn why chemistry matters, what secondary plant metabolites are and their importance. Each secondary plant metabolite is discussed in detail, covering medicinal activity, optimal extraction (with tips), and taste. Botanical examples are featured with their constituents. The explanation of each of the concepts is written in an interesting and clear way. A great chapter for science-lovers and those who are new to the subject.

Story and Ingredients

We move on to the story of bitters in the beginning of the third chapter with the authors sharing the history of different bitters formulas. I appreciated that the previous (awesome) chapter on chemistry was followed by this chapter that includes the rich traditional knowledge of bitters. The chapters really complement each other.

We are then introduced to the basic template for making bitters. This addition will guide the reader on how to create their own unique and balanced bitters formulas. The recipes in this book also follow this template.

Once the foundation of why, taste, chemistry, and tradition has been covered, we are introduced to building a bitters formula. The basic ingredients needed—herbs, alcohol, and sweeteners—are explained and easily attained in my local area. There is a resource list in the back of the book should they not be as easily attained in your own community. The tools listed are mostly common kitchen tools. I personally don’t have a juicer which is included on the list but the authors point out that a fork can be used, which is what I’ll be using. I love the grounded practicality of this tool substitution.

Basic processing is covered next with step-by-step instructions, including photographs for each of the processes- pastilles, tincture, and syrups. The photography throughout the book is beautiful and complements the text wonderfully.

The chapter continues with a detailed ingredients list or what I call the materia medica. Each of the more than 90(!) ingredients or plants—there is only one non-plant on this list: bacon. Yes, bacon—includes background, flavor, chemistry, extraction, and recipe suggestion(s) that are included in the recipe section of the book. This is an extremely well-done materia medica that builds on the topics Masé and King covered in the previous chapters.

Bitters Recipes

Now it’s time for the recipes themselves and there are a lot of them. The recipes are divided into three categories: simple daily habits, unique bitters preparations, and extract-based blends. The “simple daily habits” category includes infusions and decoctions, broth, and salads. I cannot wait to try the after-meal tea and soup stock from this category. “Unique bitter preparations” include candies, salts, pastilles, infused wine, and brandy. I made the cacao after-dinner mints as soon as I saw the recipe. I served them to both adults and teenagers, some of which apparently had previously tried not so delicious pastilles, and they were a hit. I plan on serving them throughout this holiday season. I am excited to try the milk thistle finishing salt next. The chapter closes with the recipes in the “extract-based blends” category. Your classic bitters—like Angostura—and syrups are covered with some not-so-classic ones like bacon bitters. In addition to the bitters formulas, there are recipes for cocktails and a spritzer using the bitters. The seasonal bitters recipes are a lovely addition that I will be making throughout the year.

In Closing

Guido Masé and Jovial King did a superb job writing this guide to bitters. It’s an engaging and beautiful book that is unique in that it covers bitters from an herbalist’s perspective, includes delicious recipes that aren’t just alcohol based but also can be easily enjoyed daily, and highlights the importance of bitters not just in our lives but also for the environment.

Support grassroots herbalists and buy your copy of DIY Bitters directly from Urban Moonshine.

If you really want to get it from Amazon, then use this link to support my site.

Val Paul is a book-obsessed folk herbalist and alleged enigma who resides in New Jersey. She can be found with her nose in a book, wildcrafting, keying plants, bird watching, or in the kitchen.

Rosalee is an herbalist and author of the bestselling book Alchemy of Herbs: Transform Everyday Ingredients Into Foods & Remedies That Healand co-author of the bestselling book Wild Remedies: How to Forage Healing Foods and Craft Your Own Herbal Medicine. She's a registered herbalist with the American Herbalist Guild and has taught thousands of students through her online courses. Read about how Rosalee went from having a terminal illness to being a bestselling author in her full story here.