Get weekly tips, recipes, and my Herbal Jumpstart e-course! Sign up for free today.

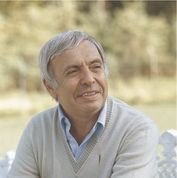

The Story of a Legendary French Herbalist: Maurice Mességué

Share this! |

|

“I make a point of asking everyone who comes to consult me: “Do you like your job?” It’s so important for the morale; a patient who is happy in his work is always much easier to cure.”

Maurice Mességué

Maurice Mességué is a French herbalist who began practicing in earnest in 1947, a time when there were virtually no herbalists in North America. He primarily used hand and foot baths to administer herbs and was a champion of carefully harvested and prepared herbal medicines.

I write this article using only two sources, both of them Mességué’s own books, which were written decades ago. So, essentially, what follows is my summary and pondering of Mességué’s written work and I cannot substantiate whether or not his amazing story is 100% fact.

Maurice

Mességué is the author of numerous books. The two I referenced for this

article include his autobiography and a book of materia medica. The

title of his autobiography is Des hommes et des plantes, which is

translated both as Of Men and Plants and Of People and Plants, and was

written in 1970. His book of materia medica is the Health Secrets of

Plants and Herbs and was written in 1975.

Mességué’s Roots

Born in 1921 in southwestern France, Mességué learned to use plants to heal ailments from his father, who had learned it from his grandmother and so on down their ancestral line. His autobiography begins by saying, “To know a river you have to know its source.” And for him, that source was his father, Camille Mességué.

Camille Mességué seems to have been a naturalist. He never did much work (for wages) and Maurice describes him as an observer of nature. He was known for several miles around (a great deal of distance before modern transportation) as a healer and helped a couple of people a month with their various ills. He also was a water diviner (using a witch hazel wand) and a hunter. He never accepted money for his herbal treatments or his water divining.

Mességué recounts his first lesson on herbal baths from his father. He was just a young boy and was having trouble with sleeping. His parents laid out a large copper basin and filled it with linden (Tilia sp.)-infused water. Maurice likens the deep sleep following a linden bath as a “drug- induced sleep”.

To heal people Camille Mességué used about forty different plants, hot water and laughter. He harvested and prepared all of the plants himself, taking great care to harvest at the appropriate times. He preferred harvests during times of the new moon. He tells the young Maurice, “My boy, remember, never [harvest] when there’s a full moon; moonlight saps their strength. For plants to be at their best they need plenty of sunshine and very little moonlight.”

Rosemary growing on a thousand year old wall in southern France

Rosemary growing on a thousand year old wall in southern FranceWhen Maurice was 11 years old his father died by accident from a self-inflicted bullet wound. Mességué was put into boarding school, where he was ridiculed and almost entirely friendless for three years. During that time he clung to the memory of his father, repeating in his head all that he had taught him about plants. Plants were his only solace; he harvested them, made teas from them, and kept them near him to remind him of his heritage.

In his youth Mességué never imagined himself taking up his father’s healing methods and certainly never imagined it would be his career. His father never took money for his “cures”. But he was occasionally questioned about using plants for medicine because of the reputation of his father. According to Mességué he was summoned one day to administer to Admiral Francois Darlan, who was in charge of the entire French Navy. This was to be the first of many famous people Mességué would attend to.

In 1944 Mességué was recruited for the STO or Service du Travail Oligatoire (Forced Working Parties). The STO was a “deal” between Germany and France: for every 3 French people who went to Germany to work one French prisoner of war was released. Mességué was forced to pack hurriedly and was escorted to board the train to Germany. He obligingly went in one door of the train and then promptly walked out another. After escaping the STO he said the only thing left to do was join the maquis, the guerrillas who fought for the liberation of France.

He survived the war efforts and in 1945 found himself as a teacher at a school in Bergerac, France. One day he came across a student who was suffering from a severe stomach ache. He gave him plants as a poultice and the next day the student was well again. Overtime he became known as a healer amongst his students. The students shared their “cures” with their parents and, before long, Mességué was seeing 15 patients a week! Upon learning of his administrations, the principal of the school was enraged and accused him of taking advantage of the parents. He ordered him to quit his herbal consultations at once. Mességué was outraged, especially since he hadn’t charged for any of his advice or herbs. He promptly left Bergerac and headed to Nice to take up his calling as a healer. He chose this town because an old friend of his father’s, who was also a doctor, resided there.

Becoming an Herbalist

Mességué headed to Nice with his head filled with exciting ideas. He would find his father’s friend and ask him for referrals. He would be in practice in no time! Upon meeting with the doctor shortly after arrival he was immediately rebuked. The doctor warned him he would be crazy to try to set up shop without a diploma. At this point in time Mességué had no understanding that one needed to be a doctor or have a diploma in order to help people. In two years time he would become very familiar with the legalities of practice.

Undeterred, Mességué found lodgings in Nice and had business cards made up, which he promptly posted to the front door of his residence, naively thinking he would be booming with business in no time. Months went by with not one patient and when his money grew short he got desperate.

Not having money for food Mességué asked a homeless beggar for tips on getting free meals. The man took him to a soup kitchen. While eating his soup Mességué noticed the man was covered in dry eczema, which he constantly itched. Mességué offered to treat him, but the man refused. Finally Mességué, knowing the man’s affinity for wine, said he would give him a bottle of wine every time he came to his apartment for a treatment (hand and foot baths). The man agreed and soon the eczema was gone. Nuns, who had previously taken care of the man, noticed the incredible improvement in his skin and began to start seeing Mességué for their own illnesses. Word of mouth quickly spread and he found himself with more patients than he could deal with.

Rising in Fame

“I was often consulted by the professional classes. These are the intellectuals, the people who feel the need to get ‘back to nature,” who do not blindly admire progress for the sake of progress. They’re afraid that science is overreaching itself and they often stop and wonder: Where is the world heading? What are we playing at?”

Maurice Mességué

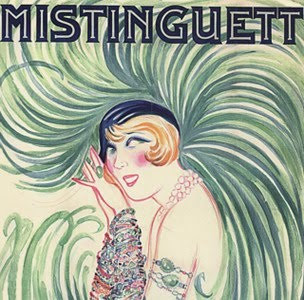

The second celebrity that Mességué treated was Mistinguette. Born in 1875 she was a famous French entertainer whose remarkable career lasted over 50 years. One could think of her as the first Marilyn Monroe. In 1919 her legs were insured for 500,000 francs! Mistinguette did not pay Mességué for his treatments; instead, she taught him the ways of high society and introduced him to many influential people.

Throughout his book Mességué claims to have treated the richest and most glamorous people of the times while also seeing a third of his clientele for free. From King Farouk of Egypt to poet Jean Cocteau to high-ranking political figures including Winston Churchill, Mességué was constantly amazed that a son of a peasant spent time with such celebrities.

Reading through his autobiography is like taking a stroll through time. As each famous person’s story was recounted I looked up the person on wikipedia to gain further insight into these movers and shakers of the 50s and 60s. Of course none of the entries mentioned Mességué.

I’ve already mentioned that the only sources of information I’ve had to go on is Mességué’s own books. I have been unable to substantiate any of the stories he tells. Conveniently, most of the famous people he treated died several years before his book was published. Or were those people specifically chosen for his book because they had passed on? While he shares the maladies and herbs given for most of the people he features in his book he withholds the treatment for some, stating he only writes about the maladies that were well known in the public eye; otherwise it is confidential.

The only factual glitch I find in his book was regarding the treatment of Pierre Loutrel, known as Pierrot le Fou (Crazy Pete). Loutrel was the “Al Capone of France” and was wanted as a dangerous criminal. Mességué claims to have treated him for an ulcer in 1950 but, according to Wikipedia, Loutrel died in 1946, a year before Mességué was in practice. Did Mességué misremember? Is wikipedia mistaken? Does that warrant a dismissal of all of Mességué’s claims? For me, I’ve chosen to believe his story and to relish the thought of an herbalist helping thousands of people, young and old, rich and poor at a time when herbalism was all but dead in North America.

Legal Battles

“The act of healing did not begin in the twentieth century. Granted that science has made such great progress, it is true nonetheless that our ancestors had discovered plenty of methods of treating various afflictions.”

Maurice Mességué

Mességué’s rise to fame did not go unnoticed. His first court case was April 28, 1949, where he was charged with practicing medicine without a license. The defense was only allowed to call 28 out of the 50 witnesses to speak in support of Mességué. He was found guilty. The trial and ruling came as a strong emotional blow to Mességué, but he barely had time to notice. The next day there were hundreds of people waiting in line to see him.

Mességué continued to practice herbalism despite the French government’s persistent opposition. He went to court over 20 times, was found guilty multiple times and had the cases dismissed a few times. Through each case he continued to raise a growing number of support. By his last court case he said there were 20,000 letters written to the judge in his favor.

Although he had strong words for some of the practices within the medical establishment, Mességué did not denounce western medicine on the whole. He very much wanted to be accepted by the doctors and to be considered one of their colleagues.

"I began to realize just how dangerous medicine can be, and when I hear of babies being treated for eczema with shots of cortisone, or year-old infants being given barbiturates, I have no hesitation in calling it criminal folly."

Maurice Mességué

His Methods

“Though my methods were sometimes puerile, I was rediscovering for myself the principle I was to apply for the rest of my life: Treat the patient rather than the disease.”

Maurice Mességué

Mességué almost exclusively used herbs in external treatments. He treated everything from arthritis to bronchitis to impotence to digestive problems with hand and foot herbal baths and poultices. Throughout his autobiography Mességué reminds us that there is no herbs for eczema; instead, he always worked with people and not their disease.

He

used a pendant to help him with diagnosis and for choosing herbs, although he states multiple times in his autobiography that he did not

place any magical belief in the pendant. He was careful not to give a

medical diagnosis, asking patients for the diagnosis of their doctor. He

does attributes many ailments to “liver problems” or “kidney

problems.”

For

Mességué the plants were of supreme importance. He felt that only wild-

harvested plants, growing far from cultivation and pesticides, that had

been dried to perfection offered the best healing abilities.

“It was equally clear to me that I couldn’t go to some unknown shop in Paris and buy desiccated herbs that would have lost two-thirds of their virtue. I had to have my own plants, I had no confidence in any others, and so I crammed my suitcase with plants and bottles.”

Maurice Mességué

Mességué refused to treat tuberculosis and cancer and he refused to treat someone under the direct care of a doctor. Instead he specialized in people whose doctors had told them there was nothing more they could do. And while Mességué claims to have witnessed many miraculous cures he is quick to state that it is the power that God put in the plants that heals, not him.

His

“Herbal”, The Health Secrets of Plants and Herbs is filled with

interesting information about some of western herbalist’s favorite

plants. His love of the plants is very evident in his writings and

immediately inspires me to book a flight to southern France to smell the

thyme and gaze on the corn poppies. One hundred plants are included in

his herbal and many have beautiful color plates as well.

“Look at lavender, or at nettles or at mint. They are modest-looking plants. One could take them as the very symbols of humility. And yet these three plants alone can deal with as many troubles as can a family medicine-chest full to bursting.”

Maurice Mességué

Mességué’s Plants

Celandine (Chelidonium majus) was one of Mességué’s most used and most revered plants.

“My father introduced me to it. He used to say that it was both the best and the most wicked of herbs. He called it swallow wort and one day he showed me how the swallows took some of the sap to their little ones in the nest to protect them from blindness. It was not till much later that I learned that the Greek word Chelidon does in fact mean swallow.”

Mességué never used this plant internally; instead it was always used as a hand and foot bath, as was his custom.

Mességué considered celandine to be a premier herb for the liver. He says it is specific for jaundice, hepatitis and swelling of the gallbladder. As a member of the poppy family, it is a sedative and can also relieve spasms of the organs.

He

goes on to say he recommends it for every case of insomnia as well as

rheumatism, gout, kidney troubles, asthma, bad nerves, chronic

bronchitis, anxiety and serious allergies. Used as a compress it works

as a vermifuge for uninvited guests in the digestive tract, ringworm and

herpes. Celandine seems to have been in practically every one of his

formulas.

Here is a description of the hand and foot baths as recommended by Mességué.

Celandine water bath

- Boil 1 and 3/4 pints of water and leave it for five minutes.

- Add a small handful of celandine flowers, leaves and roots. Let it macerate for 4-5 hours.

- When it is done, boil 3 1/2 pints of water. Let this stand five minutes and then add to the herbal brew.

- This brew can be used for eight days and can be reheated (not boiled). No new herbs need to be added to this mix.

Mességué recommends boiling the water in china. He does not recommend metal or plastic for herbal preparations.

Foot baths should be taken in the morning on an empty stomach. The water should be as hot as possible. The bath should last no longer than 8 minutes. Hand baths are taken in the evening before dinner. Again they should last no longer than 8 minutes and the water should be as hot as possible.

Celandine

CelandineMességué’s Accomplishments

Mességué practiced herbalism from 1947 on and saw tens of thousands of patients.

In 1958 Maurice Mességué created the Wild Herbs Laboratories, which later became the Mességué Laboratories. It was the first herbal business to be strictly “organic” and denounce any use of pesticides. The business still exists but I believe it has now been sold. http://www.Messegue.com

But I can promise you one thing-you won’t find the slightest trace of any chemicals. My herbs have grown free in their chosen soil, where nature intended them to grow. They were happy plants, and that’s important. When you’re happy you’re at your best.

Maurice Messsegue

In 1971 Mességué was elected the Mayor of Fleurance, a small town in southwestern France and home to his retail herbal store. He continued to serve as the chief magistrate until 1989.

He is the author of at least ten books, not all of which have been translated to english.

In 1994 he created the Institute of Maurice Mességué to continue his work. (I found a listing and address in a French directory but was unable to learn anything more.)

Italy

hosts five different spa and wellness centers that give treatments

based on Mességué’s methods, including hand and foot baths and his

dietary regimens. They are called the Centres de cure Maurice Mességué.

One of these is run by his son, Marc Mességué.

Conclusion

Maurice Mességué was a pioneer of herbalism. He was practicing in France at a time when herbalism was all but dead in North America. He is a strong voice for the plants, reminding us the best remedies grow outside our door, and include our common weeds as well as fresh air and sunshine. Mességué is still living and is in his 90s.

I hope that by writing this book I am leaving a message for future generations. Let us hope that the destruction and pollution that our civilization wreaks upon nature will be brought to a halt; let us hope that our children in their turn will have the chance to admire the cornflower and the poppy and the wild rose and rejoice in their beauty... before they use them to ease their complaints!

Maurice Mességué

Resources

If you've enjoyed learning about Mességué, then I highly recommend going to the source. The two following books are the ones I cited in this article.

Of People and Plants: The Autobiography of Europe's Most Celebrated Healer

Health Secrets of Plants and Herbs

This article was originally published in the Plant Healer Magazine.

Rosalee is an herbalist and author of the bestselling book Alchemy of Herbs: Transform Everyday Ingredients Into Foods & Remedies That Healand co-author of the bestselling book Wild Remedies: How to Forage Healing Foods and Craft Your Own Herbal Medicine. She's a registered herbalist with the American Herbalist Guild and has taught thousands of students through her online courses. Read about how Rosalee went from having a terminal illness to being a bestselling author in her full story here.