Get weekly tips, recipes, and my Herbal Jumpstart e-course! Sign up for free today.

Benefits of Comfrey

Share this! |

|

The benefits of comfrey are soooo many, but it’s also one of the most controversial herbs out there. In this episode, I’m sharing safety tips for working with both comfrey root and comfrey leaf. Plus, I’ll be showing you exactly how to make a deeply healing comfrey plant poultice.

Worked with correctly, comfrey is a powerful healing ally. But work with it incorrectly and you could end up doing more harm than good… thus, the controversy over comfrey safety.

After this episode, you’ll know:

► Important safety considerations for working with comfrey

► When comfrey is NOT the right herb to apply to a wound

► How to have a fresh comfrey leaf poultice on hand even in winter

This is one episode you don’t want to miss!

-- TIMESTAMPS -- for the Benefits of Comfrey

- 00:00 - Introduction to the comfrey plant

- 02:24 - Comfrey energetics

- 03:59 - Comfrey plant for healing tissues

- 06:36 - Comfrey for musculoskeletal pain

- 08:52 - Is comfrey toxic?

- 16:13 - Summary: Working with comfrey medicine safely

- 17:19 - How to identify the comfrey plant

- 18:33 - Tips for growing comfrey

- 18:58 - Comfrey look-alike to avoid

- 19:25 - Using comfrey roots and leaf safely

- 21:28 - How to make a comfrey leaf poultice

- 24:59 - Comfrey Fun Fact

Download Your Recipe Card

l

Transcript of the Benefits of Comfrey Video

People have long been amazed by the benefits of comfrey to heal wounds and broken bones. In the 17th century, herbalist John Parkinson said that comfrey was so amazing for knitting together flesh that if you put two pieces of severed flesh in a pot with comfrey, they would be joined together again.

To be honest, I haven’t tried this myself… and while I doubt that really works, I have no doubt that comfrey is a powerful wound healer – I’ve seen it work many times with my own eyes.

Do you have experience with the benefits of comfrey? I’d love to hear about it in the comments at the bottom of this page. Your comments mean a lot to me! I love cultivating a community of kind-hearted plant-loving folks! Plus, it’s always interesting and insightful to hear the experiences of plant lovers out there. Your suggestion may also help others!

Okay, let’s dive in…

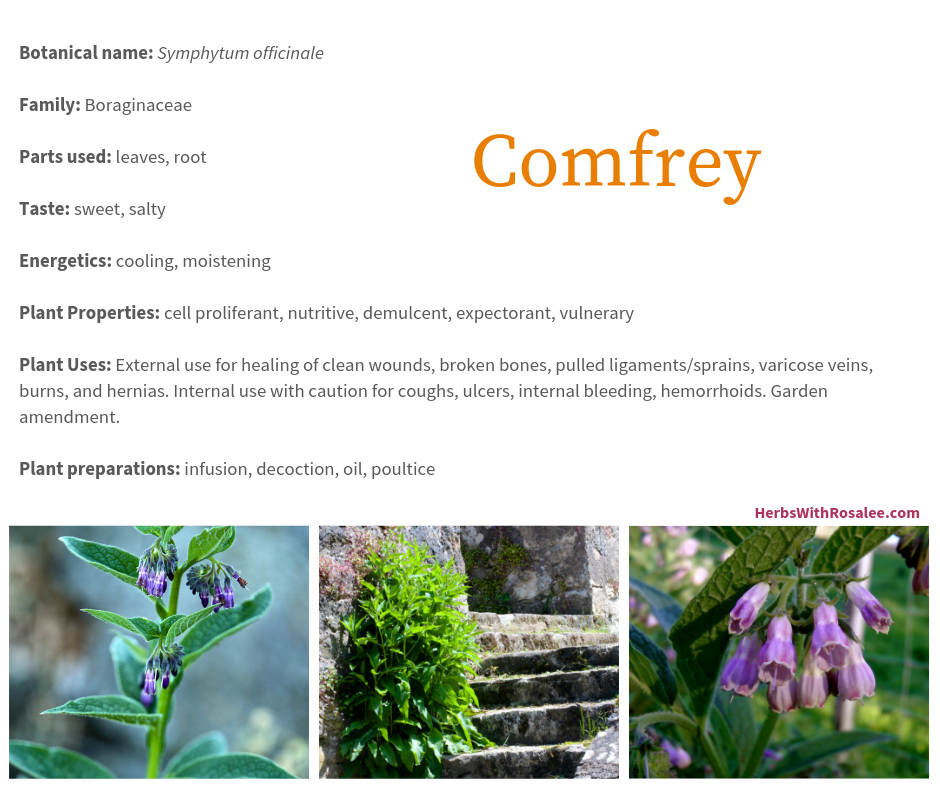

Benefits of Comfrey: Comfrey Energetics

The comfrey plant is both cooling and moistening. It’s often indicated for hot and dry conditions such as a burn.

If you’re unfamiliar with the term herbal energetics, this is simply looking at the qualities of a plant in regards to it being hot or cool and damp or dry and then matching those qualities to a person or a condition.

So in this case, the hot stinging qualities of a burn, whether it’s a sunburn or a minor burn from cooking, are relieved by the cooling and moistening qualities of comfrey.

Comfrey is also an amazing healer of tissues, which I’m going to share lots about in just a minute. Its cooling abilities are wonderful for modulating inflammation of the musculoskeletal system, especially when there are signs of heat and dryness.

As a side note: turmeric often gets a lot of praise, and rightfully so, for being a powerful plant for the musculoskeletal system. But turmeric is a bit warming and it’s very drying, so not always a great match when you already have a lot of signs of heat and dryness. Comfrey could be another great choice.

My first book, Alchemy of Herbs, shows you exactly how to choose herbs that are best for you, based on herbal energetics. So if these concepts are new to you, check out that book to get a foundational understanding that will dramatically increase your effectiveness with herbs.

Benefits of Comfrey for Healing Tissues

Above all, comfrey is a supreme healer of the body’s connective tissues, including mucous membranes, fascia, the skin and bones. It works amazingly well for everything, from little scratches and rashes and boo-boos, to more serious cases such as eczema, skin ulcers, sprains, broken bones, rheumatic complaints, and healing from surgery.

Most herbalists have amazing comfrey tales to tell and I’ve racked up a few of my own over the years. I’ve seen my mother-in-law avoid knee surgery (to the amazement of her doctor), a second-degree burn on my thumb that was immediately soothed and then completely healed within 24 hours, and countless minor cuts and bruises restored in record time.

But you don’t just have to take my word for it – there are multiple clinical trials validating comfrey’s wound healing abilities. In one randomized double-blind clinical study, 278 patients used either a comfrey cream or a placebo on fresh abrasions. Those using the comfrey cream healed almost three days faster than those using the placebo.14 Comfrey has also been shown to work well for healing bruises and contusions in children.15

How does it work? Comfrey is a cell proliferant. It increases cell growth and rejuvenation, thus propelling the healing action of the body. Many times, one chemical constituent, allantoin, a known cell proliferant, gets all the credit for this ability.

However, one study compared the healing abilities of a water extract of comfrey root vs. pure allantoin and concluded that, “the biological activity of the comfrey root extract cannot be attributed only to allantoin, but is also likely the result of the interaction of different compounds present in AECR [aqueous extract of the comfrey (Symphytum officinale L.) root].”16

Comfrey can also powerfully heal burns. I would never want to be without it, as it has soothed many of my own minor burns since.

I’ve also seen the topical use of comfrey significantly address swelling. An acquaintance of mine was stung by a wasp and, as a result, her arm had significant swelling. By the time she asked for my advice, it had been swollen for days. She ended up using comfrey as a bath for her arm, and the swelling reduced almost immediately.

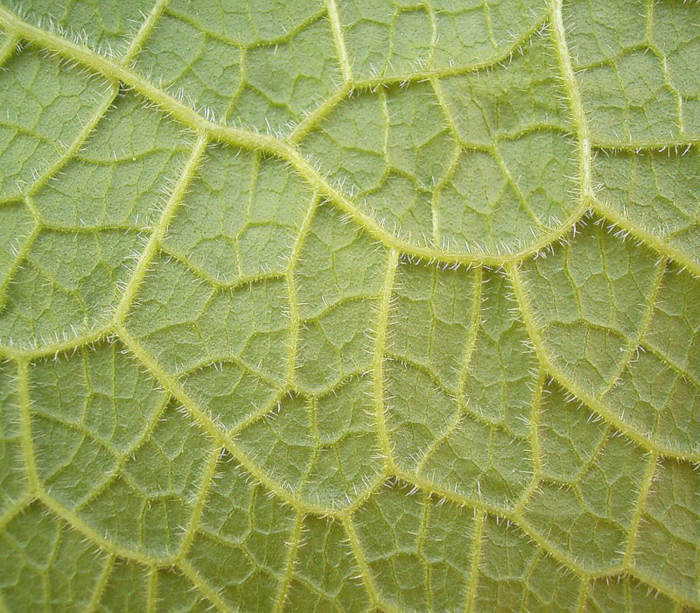

The Underside of a comfrey leaf

The Underside of a comfrey leaf By Frank Vincentz (Own work) [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html) or CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/)], via Wikimedia Commons

Benefits of Comfrey for Musculoskeletal Pain

Comfrey’s ability to modulate inflammation and decrease pain in musculoskeletal injuries and general pain dysfunction has also been well studied. In one randomized, controlled, double-blind clinical study, a topical cream made with comfrey was used for patients with general back myalgia (muscle pain). Those using the concentrated comfrey cream had decreased pain on active motion during rest and palpation, and healed faster than those using the reference product.17

In another clinical trial with patients who had low back pain, 95.2% of those using a topical comfrey cream had decreased pain, as opposed to 37.8% of those using the placebo cream.18

Comfrey has been shown to decrease pain and swelling in acute trauma. In one controlled, double-blind, randomized multicenter study, 203 patients with ankle sprains were given either a comfrey cream or a placebo cream to use topically. Patients using the comfrey cream saw a highly significant decrease in pain and swelling by days three and four.19

Comfrey root has been shown to be effective for patients with osteoarthritis of the knee. One randomized, double-blind, bicenter, placebo-controlled clinical trial followed arthritis patients who used a comfrey cream daily for three weeks. Those using the comfrey cream had significant improvements over those using the placebo. They concluded that, “The results suggest that the comfrey root extract ointment is well suited for the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee. Pain is reduced, mobility of the knee improved, and quality of life increased.”20

As you can see, comfrey is a powerful healer! But, as I mentioned earlier, the comfrey plant is also highly controversial. So let’s look into that more deeply in this next section.

Benefits of Comfrey: Is Comfrey Toxic?

Mention the benefits of comfrey in a room full of herbalists and you’ll most likely be front-row seat to a heated discussion. Everyone’s got an opinion regarding the safety of comfrey, and most herbalists aren’t shy about expressing it.

For years, I’ve watched the comfrey debate from afar, and noted that many people will refer to someone else when justifying their opinions. They’ll say, “So and so says comfrey is safe, so it must be true.”Or they’ll say, “Well, this other person says it’s not safe so that must be true.”

While I have no doubt the comfrey debate will continue on for a long time, I want to address this issue as objectively as possible by looking at what evidence we have of its safety and what evidence we have of its potential for harm. My hope is that people will have a better understanding of the complexities of this herb, rather than simply relying on what others have said.

In the end, my goal is that you can feel confident about using the roots and leaves safely.

There are three main considerations when looking at the safety of comfrey.

#1. The level and type of alkaloids in the comfrey plant you’re working with.

#2. The type of medicine you’re making with comfrey.

#3. The health of the person using comfrey.

Let’s look at each of these more in depth.

The first consideration is… what exactly is in the comfrey plant you’re working with. Here’s what I mean by that.

Comfrey has been shown to contain pyrrolizidine alkaloids (PAs), which are substances that we know are potentially toxic to humans by causing liver damage. There are over 600 different PAs that have been identified in over 6,000 plants.1 Many PAs are harmless, but those that are harmful take quite a toll on the liver, causing veno-occlusive liver disease and/or liver cancer. PAs are found in the borage, aster, orchid and pea families and are a plant’s defense against being eaten by herbivores.

The main concern regarding humans and comfrey is veno-occlusive disease or VOD. This condition happens when the very small veins of the liver are obstructed, preventing normal liver function and causing a backup of blood in the liver, leading to engorgement, portal vein pressure, fluid buildup in the abdomen, enlarged spleen, and liver scarring (cirrhosis). Symptoms occur very quickly. About one-fourth of the people diagnosed with hepatic VOD die.2

We know without a doubt that all species of comfrey contain varying levels of several different types of PAs.3

The two most often discussed species of comfrey are Symphytum officinale (common comfrey) and Symphytum x uplandicum (Russian comfrey, a hybrid). We know that Symphytum x uplandicum contains more PAs than Symphytum officinale.4 However, because plants can easily hybridize within the genus, it’s hard to say whether a given plant has a certain level of PAs unless that exact plant has been tested.

One set of tests done in 1980 showed that there were significantly lower levels of PAs in Symphytum officinale leaves after the plant had matured and gone to flower. Studies also show that the leaves reliably have fewer PAs than the roots.5

Okay, to sum this up. All comfrey plants have some level of PAs. Those levels can differ dramatically between various plants and hybrids, the maturity of the plant, and even the plant part.

The second consideration is what kind of medicine is being prepared with the comfrey plant.

When it comes to the benefits of comfrey, internal medicines like teas and tinctures are always going to carry a greater risk than using external medicines like poultices, salves, and soaks. (I’ll be showing you my favorite poultice preparation in just a bit.)

Teas, or water-based extractions, are going to have fewer alkaloids in them because water is a weak extractor of alkaloids. Tinctures, or alcohol-based extractions, are going to have more alkaloids because alcohol is a stronger extractor of alkaloids.

Sometimes you’ll hear claims that water extractions (such as teas) do not contain PAs.

However, in one analysis of herbal teas made from the leaves of comfrey (Symphytum officinale), we see that there are PAs present in the tea.6

If you know me at all then you’ll know that I love it when we can make food our medicine. Comfrey leaves are high in vitamins, minerals, and even protein. The leaves of this plant were also once widely eaten as a wild green food but while there is an historical tradition of eating comfrey, what we now know about PAs makes this a bit problematic.

As a rule, I avoid citing unethical animal studies in my articles. There have unfortunately been a number of studies of comfrey involving rats. I will not cite them here, but only acknowledge they exist and that when you feed rats large amounts of comfrey, they will get a liver tumor.

I have heard herbalists point out the flaws of using these studies (e.g., rats are not humans, the dosage was insanely high) and then claim that since these studies are flawed, then comfrey must be safe. The reality is, even if you completely disregard these animals studies, there is still evidence that comfrey is potentially harmful to humans. In the same light, using only these flawed studies to proclaim comfrey dangerous is misleading.

To date, there have been no human clinical trials regarding comfrey ingestion. Since there are concerns about comfrey toxicity, you can imagine the ethical considerations a human clinical trial would raise.

Which brings us to our third consideration. The health of the person working with comfrey.

There are some people today who love comfrey and regularly drink comfrey tea, seemingly without issues. Before the potential for toxicity was known, comfrey root was used internally for many hot conditions, such as dry, irritated lungs. It was also used for internal bleeding of the lungs and digestive tract, such as ulcers and hemorrhoids.

There are also some cautious human case studies regarding comfrey consumption. In all of these case studies, comfrey does appear to have caused problems, but there are also multiple confounding factors, such as concomitant use of hepato-toxic drugs and malnutrition.8,9,10,11

You can read more about these case studies here.

Okay, let’s sum this up…

All comfrey plants contain some level of PAs but it’s hard to know exactly how much unless you get that actual plant tested.

The method that you use to prepare comfrey matters. External use of comfrey leaf and root is far safer than internal use. Teas are going to be safer than alcohol extractions. Mature leaves will be safer than roots.

And lastly, a big unknown is how individuals might respond to PAs as there can be a lot of individual circumstances that make one person more susceptible than another.

Without a doubt neither comfrey root nor leaf should be used during pregnancy, breastfeeding, or in small children with developing livers.

So, after that summary, I’ll just say that my personal take is that I don’t feel that it’s ethical to recommend this plant internally until we know more about how to use it safely for everyone.

Benefits of Comfrey: Botanically Speaking

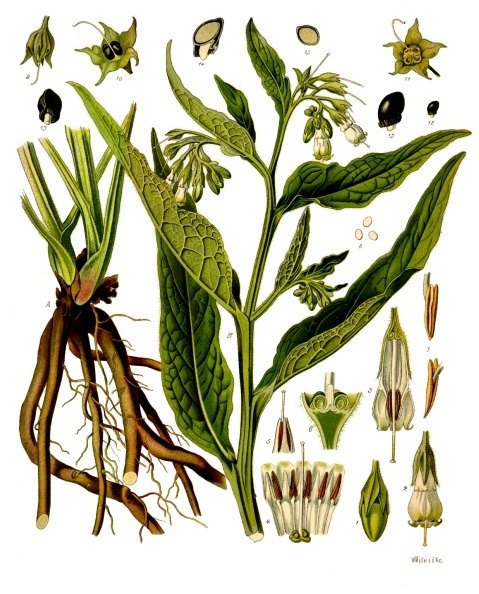

Comfrey is native to Europe and Asia and likes to grow in sunny moist areas. There are many species of comfrey in the Symphytum genus.

Symphytum officinale (common comfrey) is most often used as medicine. Symphytum x uplandicum (Russian comfrey, a hybrid) is more often used as a garden fertilizer and animal feed. This section describes Symphytum officinale.

Comfrey is a hardy perennial with a strong root base. This plant is practically impossible to kill in temperate regions. You can hack away all of its leaves and even part of its root and it will still grow back.

The leaves are oblong and coarsely textured, with smooth margins.

It flowers in the late spring to summer, with flowers ranging from pink to blue to purple. The flowers are small and bell-shaped, typical of the Borage family. Bees love the flowers.

It can grow up to four feet in height.

Comfrey is easily grown from seed or root cutting in temperate zones. Once you have comfrey in your garden prepare to always have comfrey in your garden. Because even the smallest piece of root can continue growing, it’s practically impossible to remove it entirely. If you want to grow it, either plant it in its forever place or consider growing it in a very strong and large container.

As always, it’s important to correctly ID any plant you’re working with. Knowing common look-alikes can help you avoid serious mistakes.

Before the plant flowers comfrey leaves can look a lot like foxglove or Digitalis spp. Mistaking foxglove for comfrey has caused fatalities as foxglove can cause serious heart issues when taken internally.

Benefits of Comfrey: Comfrey Uses

The safest way to use comfrey is with external applications, including poultices, salves, and fomentations/washes. These preparations are ideally made from the fresh leaves and/or roots.

Just to be super clear, here are a list of comfrey considerations:

All species of comfrey contain pyrrolizidine alkaloids (PAs), which can potentially cause serious damage to the liver when taken internally. The mature leaves of Symphytum officinale contain the lowest amount of PAs. The young leaves and roots contain the most PAs.

As a result, comfrey should never be used internally during pregnancy, breastfeeding, or in small children with developing livers.

Some herbalists recommend using the mature leaves as a tea for short periods of time, for example 1-2 weeks, during healing of a broken bone or traumatic injury. While many people do this with no known adverse effects, there is a rare but real risk depending on circumstantial factors (as shared earlier, these include the levels of PAs in that particular plant, health of the person drinking the tea, etc).

Comfrey used topically is considered safe in regards to the PA toxicity concerns.

However, comfrey should not be used on infected or dirty wounds (especially puncture wounds), because it may heal the skin without eliminating the infection.

Because of comfrey’s amazing cell proliferation effects, there are concerns that using comfrey topically over a broken bone that hasn’t been correctly set may heal the bone out of place.

Benefits of Comfrey: Comfrey Leaf Poultice

When used safely, comfrey is hands down the most healing plant for wounds, burns, injuries, and even musculoskeletal pain.

It works so well that you have to be cautious and only apply this poultice to clean wounds without any sign of infection such as excess redness, itching, swollen, heat, pus, and to bones that have been set. Comfrey is said to work so quickly that it can seal in infection and heal bones out of place! However, when used correctly, you’ll find that there is no better stitcher upper than comfrey.

The following comfrey poultice recipe was written for our book, Wild Remedies: How to Forage Healing Foods and Craft Your Own Herbal Medicine. However, this recipe never made it to the book because we had to edit it down for length! So you can consider this a bonus recipe!

If you don’t already own Wild Remedies, this is an essential guide to learning about the edible and medicinal gifts of the plants that grow around you!

You can find it wherever books are sold and then visit WildRemediesBook.com to register for your exclusive bonuses like a three-part documentary highlighting many herbalists like Rosemary Gladstar, Robin Rose Bennett, Guido Masé, and Marc Williams.

Here’s what you’ll need to make the poultice:

- 2 cups fresh comfrey leaves and small stems, roughly chopped

- About 1/4 cup water

1. Place the leaves in a small food processor or blender.

2. Turn on the machine and slowly drizzle in about ¼ cup of water. You want the leaves to form a thick mixture without being too runny.

3. Once it is well blended, use a spatula to scrape it into a small bowl.

If you are going to use it immediately then you can spread the mixture thickly over the affected area and then wrap with a clean gauze or bandage or an old t-shirt. Change this every 1 to 3 hours.

You can also freeze this for year-round use. There’s a couple of ways to do that. The first is to simply freeze it in ice cube trays. Once frozen, pop out the cubes and store in a freezer-safe bag and be sure to label them with the contents and date. Or, the paste can be simply frozen in a freezer-safe bag; for best results, use a vacuum pack sealer. Again, be sure to label it well. I recommend using it within a year.

You can use this same method for preparing a poultice with the roots.

Benefits of Comfrey Fun Fact

Comfrey is commonly used in regenerative farming and gardening practices. The leaves can be used as a mulch, added to the compost pile, or fermented down to a dense green liquid to be used as a potent fertilizer. The hybrid, Symphytum x uplandicum, is often used for this, but any comfrey will do. Comfrey is also being explored as a nutritive forage food for animals.

If you enjoyed this video on the health benefits of comfrey and you value trusted herbal information, then I hope you’ll stick around! The best way to get started to subscribe to my newsletter at the bottom of the page so you can be the first to get my best herbal insights and recipes.

Citations for Benefits of Comfrey

Click to show/hide.

Rosalee is an herbalist and author of the bestselling book Alchemy of Herbs: Transform Everyday Ingredients Into Foods & Remedies That Healand co-author of the bestselling book Wild Remedies: How to Forage Healing Foods and Craft Your Own Herbal Medicine. She's a registered herbalist with the American Herbalist Guild and has taught thousands of students through her online courses. Read about how Rosalee went from having a terminal illness to being a bestselling author in her full story here.