Get weekly tips, recipes, and my Herbal Jumpstart e-course! Sign up for free today.

Dandelion Herb Benefits

Share this! |

|

For many herbalists dandelion is much more than a nutritious weed, it’s also a symbol of a plant revolution. Despite being hated and poisoned by lawn purists, dandelion continues to thrive. It breaks through cement cracks, covers entire fields, and spreads billions and billions of seeds over the earth every year. This is one powerful plant.

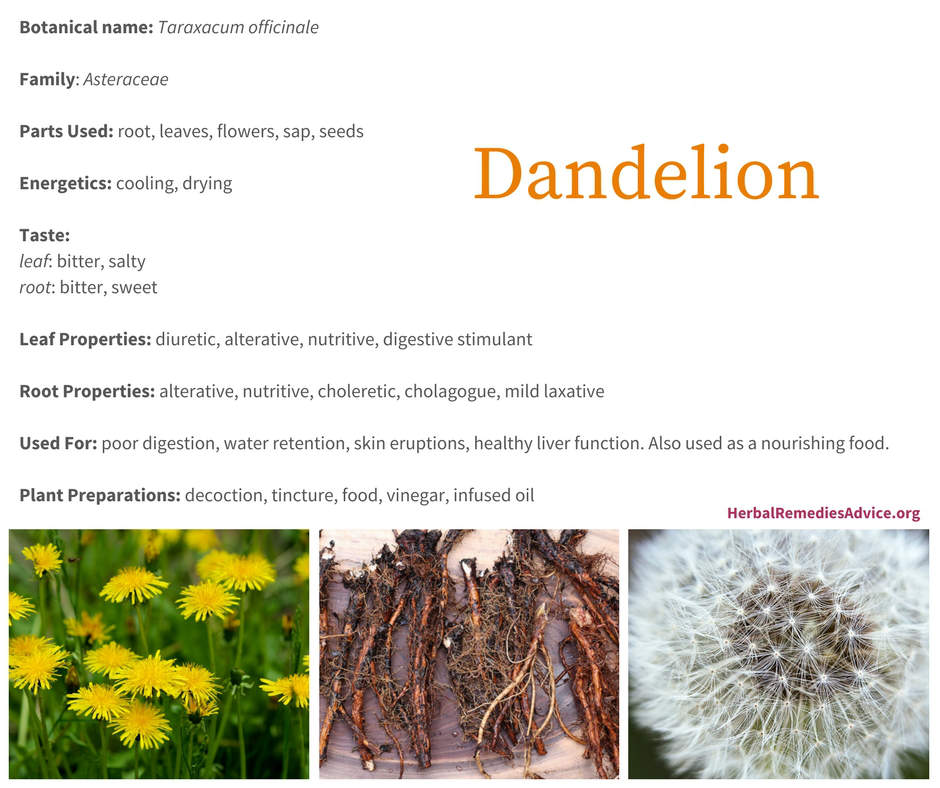

Dandelions are also a reminder that a simple and common weed can offer us important gifts as both food and medicine. All parts of the dandelion are beneficial in some way or another. This article will look at dandelion from the ground up to explore the roots, leaves, stems, flowers, and seeds as food and medicine.

Dandelion Herb Benefits: Dandelion Facts

Dandelion is an opportunistic plant originating from Eurasia, which has spread to all temperate climate zones of the world. Europeans have long loved the plant as both food and medicine, and most likely intentionally (and unintentionally) brought the seeds with them to North America, where dandelion quickly spread. Anita Sanchez, author of The Teeth of the Lion, reports that a New England botanical survey done in 1672 lists dandelions as well-established. Sanchez also says that the plants were introduced to Canada by the French and to the west coast by the Spanish.1

It wasn’t until the mid-19th century that the rise of the perfect lawn evolved into a common disdain for this beautiful plant. Today, consumers spend billions of dollars on herbicides for their lawns, mostly to eradicate dandelions.

Dandelion root was in the United States Pharmacopoeia from 1831-1926. It remains in the pharmacopoeias of Austria, Hungary, and Poland.2

Dandelion Root Benefits

Dandelion roots are tenacious. If you harvest only a part of the root, the plant will heal itself and keep on growing! This fortitude is the bane of lawn lovers and a generous gift for those of us who adore dandelions.

Dandelions send their long roots deep into the earth, pulling vitamins and minerals into the plant. Fresh dandelion roots have a sweet and slightly bitter taste and they make a wonderful nutrient-dense food.

Besides being high in micronutrients and phytonutrients like iron, manganese, carotenes, calcium, and potassium, dandelions are also high in inulin.3 Inulin is a starchy carbohydrate that can help restore healthy gut flora in an interesting way. While we can’t break down this substance ourselves, eating it regularly provides food to the gut microbiome. Think of it like this: is a seed more likely to grow if you drop it on the cement? Or is it more likely to grow if you drop it into a rich soil and regularly add compost and water? The same goes for your gut flora. As a result of its beneficial effect on gut flora, inulin is often called a PREbiotic.

Dandelion roots also are important medicine. Many herbalists use dandelion roots to support liver health. Matthew Wood suggests the root specifically for “Liver congested, swollen, gallbladder congested, bile thick, adhesive, gallstone formation, lack of bile secretion, jaundice from back-up bile, constipation from lack of bile in the intestines; anemia from lack of bile production and recycling.”4

While we don’t yet have a scientific understanding of the way dandelion root affects the liver, we do have important energetic distinctions. When liver health is disrupted it can show signs of heat, signs of stagnation, or both.

I consider symptoms of liver stagnation to include poor digestion (especially poor fat digestion or absorption), sour belching, estrogen dominance, and excessive PMS symptoms (including bloating, clots, cramping, irregular bowel movements, and excess anger).

If Liver Stagnation isn’t resolved, it can further evolve into what Traditional Chinese Medicine practitioners call Liver Heat. Signs of Liver Heat include red tongue (especially on the sides of the tongue), headaches behind or around the eyes, dry mouth, bitter taste in the mouth, tinnitus, bursts of anger, hot and itchy skin conditions, and dry and red eyes.

Dandelion root is gently stimulating, moving stagnation and generally improving liver health. I think of dandelion as giving a firm and steady tap to the liver to nudge it back into healthy function. It is both cooling and draining, which makes it specific to the hot and damp conditions that the liver is easily prone to. In herbal terms, dandelion root is considered to be both a choleretic herb (affects the liver) and a cholagogue (affects the gall bladder).

Because it improves liver function, dandelion root has rippling benefits for many symptoms associated with poor liver health, including acne, boils, and PMS. Because of its wide ranging effects, specifically in regards to removing stagnation, dandelion is often referred to as an alterative herb.

Herbalists have used dandelion for arthritis symptoms for centuries and modern researchers have tried to find the mechanism of action. In one in vitro trial, an extract of dandelion, taraxasterol, has been shown to decrease inflammation and protect healthy cells. The authors of the study concluded: “Taraxasterol may be a useful agent for prevention and treatment of OA [osteoarthritis].”5

Dandelion root has historically been used to support people with cancer. Herbalist Michael Tierra uses it alongside burdock and other herbs for his cancer patients. He says, “I’ve studied literally hundreds of herbs from around the world, and considering cost, availability, palatability (no small matter, as people with chronic disease like cancer need to be able to take their herbs at least three times a day for months) – there are probably no two more simple and powerful anticancer herbs on the planet than dandelion and burdock.“6

The University of Windsor in Canada is conducting “The Dandelion Root Project”. Since 2009 they have been testing dandelion extract in the lab against various cancer cells. They are currently in Phase 1 clinical trials for drug refractory (resistant) blood cancers.7

Dandelion Herb Benefits: Dandelion Leaves

Dandelion leaves have long been considered a spring tonic. When young and fresh, the leaves have a delicate bitter taste that stimulates digestion. Effects of the bitter taste on the tongue include increased saliva (helps to break down starches and carbohydrates), increased stomach enzymes (further breaks down starches and also proteins), increased bile (aids fat digestion), and stimulated natural peristalsis (to keep bowels moving).

My husband is from the French Alps and he remembers going to the fields and picking those fresh green leaves with his mother in the springtime. The bitter digestion-stimulating effect of dandelion leaf would have been an especially important effect after a long winter of the traditional rich meals of the French Alps. Dandelion leaf has important actions for our physiology today, when many of us suffer from impaired digestion and the consumption of rich foods throughout the year.

Besides helping to stimulate digestion, the leaves are also nutritious. They are especially high in calcium, phosphorous, carotenes, and potassium. Remember the benefits of inulin found in dandelion roots? It turns out the leaves also have a surprisingly high amount of inulin, and therefore have the same beneficial effect on gut flora.

Speaking of the French, they could win the prize for the country most infatuated with dandelion, as they have been actively cultivating it for centuries. We get the English common name of dandelion from the French “dent de lion,” meaning “teeth of a lion,” which refers to the jagged edges of the leaves. However, in France, the name most commonly used for dandelion is “piss-en-lit” (pronounced: peace-on-lee), which literally translates to “pee the bed.” This apt name refers to the strong diuretic qualities found in the leaves. In fact, dandelion leaves are one of the most common diuretics used by herbalists today to address edema, urinary stagnation, and symptoms of high blood pressure. Preliminary human clinical trials have confirmed the diuretic effect of dandelion tincture (alcohol and water extraction).8

Dandelion Herb Benefits: Dandelion Flowers

One of my favorite sights is a meadow filled with golden dandelion orbs in the springtime. It astounds me that people have been so effectively brainwashed to hate this joyful and beautiful plant.

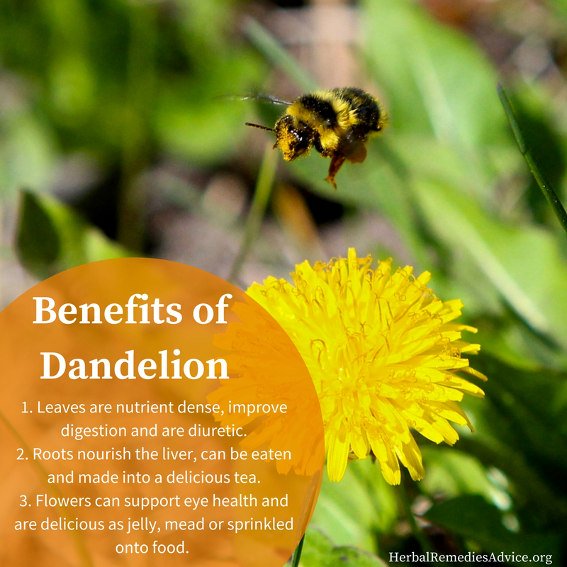

Dandelion flowers are more than a pretty face – they are edible and nutritious! The flowers are high in lutein, a constituent known to dramatically support eye health. The inflorescences can be eaten raw, fried in batter, or turned into jam or wine.

Dandelion flowers are also important for human survival. Those early spring blooms are an important food source for the honey bee which is responsible for pollinating many of our fruits and vegetables.

Dandelion Herb Benefits: Dandelion Stems

“Waste not, want not” could be the motto of the dandelion. Even the dandelion sap offers benefits to humans. If you slice open a flower stem or a mature leaf stem, the plant will exude a thick white substance that will reportedly remove warts with consistent application.

In keeping with the “waste not, want not” mantra, I came up with a recipe for Fermented Dandelion Stems.

Dandelion Herb Benefits: Dandelion Seeds

Perhaps the most obvious gift of dandelion seeds are their free wishes. Can you count how many times you’ve picked a downy dandelion seed head so that you could blow off the seeds and make a wish? I hope it’s too many times to count!

Dandelion seeds are prolific. There are over 100 seeds in every inflorescence. A small field of dandelions could easily produce millions, if not billions, of tiny umbrella-like seeds, which will easily germinate, bringing us more delicious and medicinal roots, flowers, and leaves.

While most herbalists don’t use dandelion seeds, I did learn from Cascade Anderson Gellar that the seeds can be plucked and eaten. Like most seeds, they offer a good source of protein (and perhaps some lessons in patience), despite their small size.

Dandelion Herb Benefits: How to Use Dandelions

It’s empowering to walk out into the yard and harvest an abundant and delicious plant to use as food or medicine. The plant can be harvested at any time; however, there are preferences to the plant parts and to whether you are using them as food or medicine.

Using Dandelion Roots

Harvest: I prefer to harvest these in the fall after the first frost. At this stage they are highest in inulin, making them sweeter and more nutrient dense. They can also be harvested after they’ve gone to seed in the late spring/summer or before they flower in the spring. In a pinch, harvest them at any time.

Uses: Dandelion roots can be eaten as you would any root vegetable. They can be dried and roasted to make a deliciously rich tea. They can be extracted into alcohol or vinegar. Alcohol will extract the medicinal qualities, while the vinegar will pull out the minerals, creating a nutritious addition to daily salad dressings.

Using Dandelion Leaves

Harvest: If harvesting the leaves for food, getting the tender young leaves in the spring is ideal. These leaves are slightly bitter but still palatable. When using them as a medicinal diuretic, they can be harvested at any time, although I still prefer the lush green growth.

Uses: As a food, add them to salads, cook them with other vegetable greens, or turn them into a delicious pesto. As a medicine, the leaves can be made into a tea, alcohol tincture, or vinegar extract.

Using Dandelion Flowers

Harvest: Dandelion will bloom throughout the growing season, but the most plentiful bloom happens in early spring. The flowers open for the sun, so I like to gather them in the middle morning on a sunny day. The flowers will close up after being picked, so depending on your desired use you may need to process them right away.

Uses: My favorite wild junk food is fried dandelion fritters. The petals can be eaten in salads or used to make wine and jelly, or baked into cookies and breads.

Dosage Suggestions for Dandelion Herb Benefits

- Decoction or powder: 3-15 grams

- Tincture: fresh root (1:2, 30% alcohol) 4-5 mL, three times a day

- Tea or powder:1-3 grams

- Tincture: dried leaf 1:5, 30% alcohol: 3-4 mL, three times a day

Special Considerations for Dandelion Herb Benefits

Every year billions of dollars are spent on poisons attempting to eradicate the beautiful dandelion. Be sure to harvest dandelions in an area that hasn’t been poisoned for at least three years.

Some people are sensitive to plants in the Asteraceae family, which can result in rare and usually mild reactions to dandelion.

The Dandelion Herb

Dandelions are small herbaceous perennial plants that grow in disturbed soils of temperate climate zones – from lawns to gardens to farms to roadsides to abandoned lots. It’s not uncommon to see dandelions growing through cracks in roads and sidewalks.

Dandelions have a strong taproot.

The leaves are simple, with jagged edges, and are commonly referred to as the “teeth of a lion.” They grow in a basal rosette and are smooth, lacking any significant hairs. (Many dandelion lookalikes have downy leaves or little prickles along the major vein of the leaf.)

The bright yellow flowers grow on a single leaf-less stem. (There are many dandelion lookalikes that have numerous yellow flowers on a single stem.)

Each flower head (inflorescence) contains many individual flowers (a characteristic of the Asteraceae family).

The seed head contains over 100 individual seeds. Each seed is attached to umbrella-like hairs (pappus), which help to transport it on the wind.

Summary of Dandelion Herb Benefits

I am writing this dandelion monograph in mid-April, just as the dandelions are beginning to emerge in the Pacific Northwest. Soon their blossoms will cover entire fields. Every year I anticipate the dandelion blooms and visit my favorite fields. How can anyone hate a plant that so generously brings such beauty into our world? I hope that you love dandelions. I hope that you share your love of dandelions with your herbicide-wielding friends and neighbors. Let’s restore this plant to its former glory. Can you imagine how big an impact we can have if we simply stop dumping poisons onto this gorgeous plant?

You can now watch my video on Dandelion Benefits here, which includes how to harvest dandelion and the benefits of dandelion leaves and flowers.

Citations for Dandelion Herb Benefits

Click to show/hide.

Rosalee is an herbalist and author of the bestselling book Alchemy of Herbs: Transform Everyday Ingredients Into Foods & Remedies That Healand co-author of the bestselling book Wild Remedies: How to Forage Healing Foods and Craft Your Own Herbal Medicine. She's a registered herbalist with the American Herbalist Guild and has taught thousands of students through her online courses. Read about how Rosalee went from having a terminal illness to being a bestselling author in her full story here.