Get weekly tips, recipes, and my Herbal Jumpstart e-course! Sign up for free today.

Dirt Therapy - The Benefits of Healthy Bacteria

Share this! |

|

Gardeners are happy people, especially during the growing season. We love to watch plants grow, we relish the early morning garden check-in, we feel amazed and even euphoric when we harvest a meal’s worth of vegetables, berries for our breakfast and, of course, our beloved herbs. We ignore the muscle-aching movement of bending, kneeling and lifting and, at the end of a busy day in the garden, we sit quietly as our sore and tired bodies surrender to the biggest cushion that can be found.

Science has revealed why gardeners wear goofy grins while grunting through garden work: we are inhaling a soil bacteria that aids in the production of the feel-good chemical, serotonin.

Soil 101

A brief lesson on the makeup of soil helps explain how it is we are inhaling good bacteria.

The most basic definition of soil is simply that soil is made of weathered rock fragments and decomposing organic matter (anything that was once alive). That’s what we see when we look at soil.

It may surprise you to learn that healthy productive soil consists of the following:

• organic matter, which consists of decomposing plant debris, is only 5%

• mineral content (AKA weathered rock) is about 45%

• depending on the current conditions the other two components share the remaining space of water and air

But it’s what we can’t see with our naked eyes that is the magic of soil: microorganisms take up residence in the decaying organic matter and begin the process of recycling. The living ecosystem of microorganisms make up less than 1% of soil but they are abundant and critical to the maintenance of healthy soil and thriving plants.

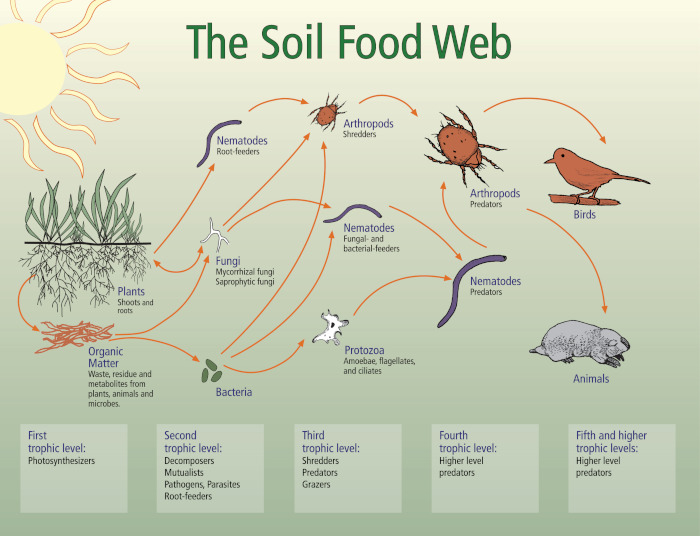

They are the microscopic workers of the soil: producers, consumers, and decomposers and their workplace is the organic matter in your soil. This abundant and invisible life includes bacteria, fungi, archaea, protists, and viruses, and we want them to hang out in our soil. This mixture of both visible and microscopic beings is called the soil food web and, in general, the more invertebrates in your soil, the healthier it is. Their work is to deconstruct (eat) and recycle (poop) every piece of organic matter.

From an Oregon State blog post titled “The Secret Life of Soil”:

“Soil is alive. Much more than a prop to hold up your plants, healthy soil is a jungle of voracious creatures eating and pooping and reproducing their way toward glorious soil fertility. A single teaspoon (1 gram) of rich garden soil can hold up to one billion bacteria, several yards of fungal filaments, several thousand protozoa, and scores of nematodes. Most of these creatures are exceedingly small; earthworms and millipedes are giants, in comparison. Each has a role in the secret life of soils.”1

Biomes and Human Health

Does this sound like another microbiome you are familiar with? Our gut biome hosts similar flora and fauna. Science is making the connection that human health is related to soil health. Healthy soil determines how nutritious your food is and now it appears that having physical contact with soil offers additional benefits. Recent research suggests that an increase in asthma and allergies may be related to a disruption in the relationship between our bodies and microorganisms found in soil. The Hygiene Hypothesis, which states that our lack of exposure to microbes has altered our immune system’s ability to develop fully, has become the research framework for studies into chronic inflammatory diseases, Type I diabetes, multiple sclerosis, cancer and some types of depression.2

Our obsession with germ-free environments is based on our understanding that bacteria make us ill and causes infectious diseases. That makes sense: pathogenic bacteria are responsible for millions of deaths around the world each year. But we now understand that non-pathogenic bacteria - the good ones - do some serious work for our guts by helping digest food, supporting our immune system, protecting us from pathogenic bacteria, assisting our digestive system and contributing to cardiovascular health.

The study of good bacteria in soil and its effects on humans is a fairly new endeavor. What Leonardo Da Vinci said five hundred years ago is probably still true today: "We know more about the movement of celestial bodies than about the soil underfoot." For several decades, the pharmaceutical industry has utilized some soil bacteria in their production of drugs for infection, tumor reduction, transplanted organ acceptance, and illnesses. More recently, research is being conducted into understanding ways that microbes affect other aspects of our wellness.

The Happiness Bacteria

In 2004, a clinical study revealed that an injection of the bacteria Mycobacterium vaccae improved the mental health of lung cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy.3 Since then, continued research has led to a proposed study of an immunizations approach that may be useful for reducing PTSD symptoms and suppressing inflammation by activating the immune system’s natural ability to regulate responses.

But we don’t need to participate in a clinical study or visit our doctors to get the benefits of good bacteria. All we have to do is interact with microbes to get more of them back into our systems. Here are some ideas to get you started:

- Start and work a compost pile. Find a corner in your yard and toss your kitchen trimmings and yard wastes into a pile. Water and turn it regularly. The compost pile is the easiest way to observe the cast of microbe characters work their magic and create an organic biome of living soil.

- Stop using sanitizing gels, antibiotic soaps, and antiseptic wipes.

- Go barefoot in the garden or on a dirt path.

- Don’t wash or peel organically grown vegetables.

- Hug your pets after a long walk - they will have plenty of microbes to share with you!

- Grow plants. Digging and watering soil moves microbes around (this is how some fungal diseases move from plant to plant) and that means you will be inhaling happiness.

Citations for Dirt Therapy

1. Support, Extension Web. "The Secret Life of Soil." OSU Extension Service. February 26, 2019. Accessed May 15, 2019. https://extension.oregonstate.edu/news/secret-life-soil.

2. "Getting the Dirt on Immunity: Scientists Show Evidence for Hygiene Hypothesis -- ScienceDaily." Science Daily. March 22, 2012. Accessed May 15, 2019. https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2012/03/120322142157.htm.

3. Obrien, M. E. R. "SRL172 (killed Mycobacterium Vaccae) in Addition to Standard Chemotherapy Improves Quality of Life without Affecting Survival, in Patients with Advanced Non-small-cell Lung Cancer: Phase III Results." Annals of Oncology 15, no. 6 (2004): 906-14. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdh220.

Sue Kusch, a former community college instructor and academic advisor, incorporates her experiential wisdom, expertise and science-based research garnered from her three decades of growing vegetables, fruit and herbs into her educational writing about plants and how people use them. In addition to her BA in Social Sciences and Masters in Education, she completed the Master Gardener training in 2011 and two permaculture courses in 2001 and 2014. She has studied medicinal and nutritional uses of herbs, including studies at Herbmentor and East West School of Planetary Herbology, since 1997. An avid reader, lover of historical and folkloric information, and a promising storyteller, Sue writes about the intersection of plants and people.