Get weekly tips, recipes, and my Herbal Jumpstart e-course! Sign up for free today.

The Mullein Plant

Share this! |

|

A few years back, I volunteered at my region’s Master Gardeners’ annual tour of local landscaped gardens. Approaching the garden at the side of one home, a tall statue of a plant with large white flowers and purple centers was blooming, and its large leaves gracefully bending from the stem grabbed everyone’s attention.

The garden owner introduced it as a mullein plant (I have since forgotten the cultivar she mentioned) and then quickly explained that it was not the “nasty invasive weed” found all over our region but a beautiful ornamental cousin of it.

I am always surprised at gardeners who quickly dismiss a plant or label it as nasty without actually taking the time to know it. Sadly, I see the same plant snobbery among my native plant colleagues who stroll right by yarrow, Oregon grape or the abundant, non-native mullein without even acknowledging their presence. If only they took the time to know the gifts that plants offer the world, perhaps they would be a bit more gracious.

My study of Common Mullein, Verbascum thaspus, quickly turned into a

deep dive into a rabbit hole - revealing a plant rich in folklore and

praised by herbalists, both historical and modern, on its many uses.

Native

to Europe, Asia, and North Africa, mullein was intentionally brought to

the Americas and Australia for its medicinal and piscicide properties.

What’s a piscicide, you ask? In mullein’s case, it’s the use of its

saponin-rich seeds tossed into a body of water for the purpose of

temporarily incapacitating fish. The fish struggle to breathe, rise to

the surface of the water and are easily caught in nets and hands by

hungry fishers.1

How to Identify a Mullein Plant

You can’t help but notice this biennial: during its first year, large, velvety leaves invite you to pet them...and then you realize why animals and insects don’t eat them! It is covered in hairs that can cause immediate skin irritation for some folks, which would be important to know should you choose to follow the recommendation to use the leaves as “cowboy toilet paper.” Apparently, the discomfort of irritated skin was overlooked by Quaker women, who, denied the use of rouge, rubbed mullein leaves on their cheeks to produce a red blush.

In its second year, the plant’s thick stem soars above surrounding plants, usually with a singular stem but occasionally with multiple extensions growing from the base stem. On the top third of the stem, flower buds resembling chickpeas in size and shape produce small, honey-scented yellow flowers, each one opening for only one day. Using a combination of insect and self-pollination, the flowers will eventually become seeds with just one plant producing between 100k - 200k seeds! The seed-filled solid stem remains standing during the winter, serving as a source of food for birds. The seeds have a remarkable survivability rate: lying dormant in the soil for years, a simple act of soil disturbance can result in what I call mullein forests - dozens of mullein plants growing only inches away from each other.

Mullein Plant Ear Oil

All but the seeds of the plant are utilized medicinally and some of the uses are rooted in folk herbal medicine. Many herbalists recommend warmed mullein ear oil for earaches in children: steep both opened flowers and flower buds in oil for several weeks and apply drops into the ears. Often the oil is blended with infused garlic oil and is used to help earaches typically associated with an ear infection.2 Herbalist and botanist, Ryan Drum, recommends using warmed mullein oil to assist with earwax-impacted ear canals.3

Musculoskeletal Uses of the Mullein Plant

American herbalist Matthew Wood utilizes mullein leaf as a remedy for swollen joints and injuries to the musculoskeletal system because of its ability to lubricate connective tissue and release synovial fluid into joint areas.4 Herbalist jim mcdonald offers his personal experience using mullein root to help align his spine after overuse.5 Taking a moment to consider the thinking behind the historical Doctrine of Signatures, that a plant that resembles a body part could be helpful as a remedy for that part, I wonder about that tall and stout stem that stands straight and its counterpart in our bodies - our spine.

Mullein Plant's Affinity for the Lungs

From the era of Dioscorides and Galen to current applications, mullein has been used to treat respiratory problems because of its expectorant, anti-inflammatory, and anti-spasmodic properties. Most of us tend to describe coughs with one word: annoying. But herbalists recognize there are different kinds of coughs and different herbs are used for treating them.

Mullein is especially useful for bronchitis and for “dry, irritable, tickly coughs - the tickle sensation is usually evidence of inflammation conjoined with water stuck in the mucosa.”6 The rest of us often describe this irritating symptom as a hacking cough.

As an expectorant, it assists the body with its natural response to eliminate mucus and phlegm by coughing. Lungs become inflamed when invaded by infection or irritants, and the demulcent properties of mullein leaves help to soothe the inflammation. Coughing can often include bronchial spasms that constrict airways, and mullein’s antispasmodic property helps to relax those airways.

The Mullein Plant, Lungs, and Wildfire

I seldom get sick with respiratory illnesses and didn’t typically keep dried mullein in my home apothecary. But then the annual seasons of wildfires started here in the Western US. Wildfire smoke can travel for miles and often contains particulates like ash. Several years ago, I woke one morning to a motionless, thick layer of smoky air from a wildfire less than a hundred miles away. Within minutes of being outside my eyes were irritated and my throat scratchy, so I headed down the road to pick a few mullein leaves. By the time I got back into the house, I had a headache developing. Though I wasn’t coughing, I wanted to be prepared in case I started. During wildfires, people with asthma and other pulmonary conditions are advised to stay inside or to wear masks if it’s necessary to be outside. Their sensitive lungs would likely react far more quickly to wildfire smoke inhalation.

To aid with respiratory complaints, mullein can be used as tea, tincture or ironically, smoked. Smoking medicinal herbs is a time-honored form of traditional medicine but many of us have developed a disdain for smoking of any kind. From a medicinal perspective it makes sense: apply the herbal remedy directly to the problem, much like we apply salve to a sore, or drink tea to settle our digestive system. My research indicates that smoking mullein is better suited to acute situations like an asthmatic attack or an intense overexposure to smoke.

Drinking an infusion of mullein leaf, fresh or dried, is the easiest way to assist your lungs, whether it’s a dry hacking cough from a respiratory infection or a spasmodic episode of coughing from being exposed to heavy smoke. Chop the leaves and steep for 10-15 minutes. Be sure to strain through a coffee filter or cheesecloth. Those hairs I discussed earlier will irritate your throat and can be as annoying as the cough you are trying to soothe. The taste is like that of many herbs: weedy. Add a splash of honey to help make the medicine go down. Drink throughout the day.

Relax and Replenish the Lungs Mullein Tea Recipe

Here’s a mullein tea recipe from Rosalee.

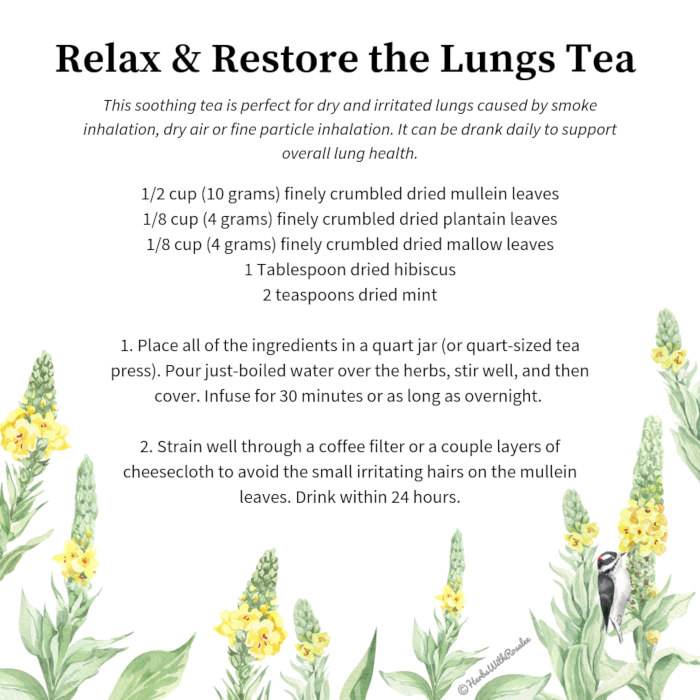

This soothing mullein tea is perfect for dry and irritated lungs caused by smoke inhalation, dry air or fine particle inhalation. It can be drank daily to support overall lung health.

Ingredients for the Lungs Mullein Tea

- 1/2 cup (10 grams) finely crumbled dried mullein leaves (Verbascum thapsus)

- 1/8 cup (4 grams) finely crumbled dried plantain leaves (Plantago spp.)

- 1/8 cup (4 grams) finely crumbled dried mallow leaves (Malva neglecta)

- 1 Tablespoon dried hibiscus (Hibiscus sabdariffa)

- 2 teaspoons dried mint (any tasty mint)

Directions for the Lungs Mullein Tea

1. Place all of the ingredients in a quart jar (or quart-sized tea press). Pour just-boiled water over the herbs, stir well, and then cover. Infuse for 30 minutes or as long as overnight.

2. Strain well through a coffee filter or a couple layers of cheesecloth to avoid the small irritating hairs on the mullein leaves. Drink within 24 hours.

Print the following handy recipe card!

Citations for Mullein Plant

Click to show/hide.

Sue Kusch, a former community college instructor and academic advisor, incorporates her experiential wisdom, expertise and science-based research garnered from her three decades of growing vegetables, fruit and herbs into her educational writing about plants and how people use them. In addition to her BA in Social Sciences and Masters in Education, she completed the Master Gardener training in 2011 and two permaculture courses in 2001 and 2014. She has studied medicinal and nutritional uses of herbs, including studies at Herbmentor and East West School of Planetary Herbology, since 1997. An avid reader, lover of historical and folkloric information, and a promising storyteller, Sue writes about the intersection of plants and people.