Get weekly tips, recipes, and my Herbal Jumpstart e-course! Sign up for free today.

What is Sumac Good for?

with Phyllis Light

Share this! |

|

I had such a great time catching up with Phyllis Light in this conversation! Hearing Phyllis’ unique herbal story and her philosophy about herbs and herbalism was a real treat. Plus, she shared such an abundance of information about what is sumac good for and its medicinal gifts that I am inspired to start working more with this amazing plant!

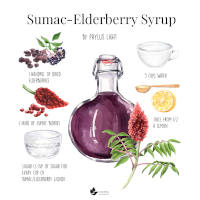

Phyllis shared so many ways to work with sumac, including her recipe for Sumac Elderberry Syrup (along with several suggestions of how to use that syrup). You can download a beautifully illustrated recipe card for Phyllis’ syrup in the section below.

You will be amazed at the many medicinal gifts that sumac has to offer! Here are just a few ways that you can work with sumac to benefit your health:

► As a topical remedy for skin issues like fungal rashes and poison ivy

► To help reduce high blood sugar

► As a cooling summer beverage that is high in Vitamin C

And that’s just the tip of the iceberg! I was delighted to learn just how many health challenges can benefit from this incredibly versatile plant. Be sure to tune in to the entire episode for all the details!

By the end of this episode, you’ll know:

► How herbalism and human health have changed in the United States since Phyllis began her herbal journey

► How to distinguish poison sumac from other species of sumac

► How to tell if your dried sumac berries are still medicinally active

► Eighteen - yes, eighteen! - health conditions sumac’s gifts can help with, and six different herbal preparations for sumac

► Why it’s so important to move beyond internet searches when learning about a new plant or herbal treatment

► and so much more…

For those of you who don’t know her, Phyllis D. Light, a fourth generation herbalist and healer, has studied and worked with herbs, foods, and other healing techniques for over 30 years. Her studies in Traditional Southern Folk Medicine began in the deep woods of North Alabama with lessons from her grandmother, whose herbal and healing knowledge had its roots in her Creek/Cherokee heritage.

Phyllis’ studies continued as an apprentice with the late Tommie Bass, a nationally renowned folk herbalist from Sand Rock, Alabama. She is the director of the Appalachian Center for Natural Health in Arab, Alabama, which offers both online classes and in-person classes. She is also on the faculty of the Matthew Wood Institute of Herbalism. Phyllis is the author of Southern Folk Medicine, Healing Traditions from Appalachian Fields and Forests published by North Atlantic.

I can’t wait to share our conversation with you today!

-- TIMESTAMPS -- for What is Sumac Good For

- 01:11 - Introduction to Phyllis Light

- 03:42 - How Phyllis found her herbal path

- 17:55 - How to distinguish poison sumac from other species of sumac

- 19:18 - Varieties of sumac that grow in Phyllis’ bioregion

- 21:58 - How to tell if your dried sumac berries are still medicinally active

- 23:12 - Harvest, drying, and storage tips for sumac berries

- 24:03 - Medicinal benefits of sumac

- 39:51 - Sumac elderberry syrup

- 48:32 - Phyllis’ current herbal projects

- 49:43 - How herbs give Phyllis hope

- 58:57 - Herbal tidbit

Get Your Free Recipe!

An immune-boosting syrup that can be canned and enjoyed over the long winter months.

Ingredients:

- 1 head of sumac berries

- 1 handful of dried elderberries

- 1 cup of sugar for every cup of sumac/elderberry liquid

- Juice of ½ a lemon

- 5 cups of water

Directions:

- Bring one head of sumac and a handful of elderberries to a boil in 5 cups of water. Reduce to a simmer for 5 minutes. Turn off heat and let sit for 10 minutes. Strain.

- Measure the strained decoction and put into a saucepan. Add 1 cup of sugar for every cup of sumac/elderberry liquid. Then add another cup of sugar for the pot. Squeeze the juice of 1/2 a lemon into the mixture and stir. Bring to a boil, then reduce to a simmer for about a minute to dissolve the sugar. Stir frequently.

- Bottle and seal into hot jars. The syrup should be a nice fuchsia color.

i

Connect with Phyllis

- Website | Phyllis D. Light

- Instagram | @phyllisdlight

- Facebook | Phyllis D. Light

Transcript of the 'What is Sumac Good For with Phyllis Light' Video

Rosalee de la Forêt:

Hello and welcome to the Herbs with Rosalee Podcast, a show exploring how herbs heal as

medicine, as food and through nature connection. I’m your host, Rosalee de la Forêt. I created

this Channel to share trusted herbal wisdom so that you can get the best results when

relying on herbs for your health. I love offering up practical knowledge to help you dive deeper

into the world of medicinal plants and seasonal living.

Each episode of the Herbs with Rosalee Podcast is shared on YouTube, as well as your favorite

podcast app. Also, to get my best herbal tips as well as fun bonuses, be sure to sign up for my weekly herbal newsletter below.

Tired of herbal overwhelm?

I got you!

I’ll send you clear, trusted tips and recipes—right to your inbox each week.

I look forward to welcoming you to our herbal community! Know that your information is safely hidden behind a patch of stinging nettle. I never sell your information and you can easily unsubscribe at any time.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

Okay, grab your cup of tea and let’s dive in.

I loved my time with Phyllis Light and it’s not simply because her information about sumac was so inspiring and eye-opening, but also hearing Phyllis’ unique herbal story and her philosophy about herbs and herbalism was also a treat. I think you’re going to love this episode, and as always, I’m excited to hear what you think.

For those of you who don’t already know her, Phyllis D. Light, a fourth generation herbalist and healer has studied and worked with herbs, foods and other healing techniques for over 30 years. Her studies and traditional Southern folk medicine began in the deep woods of North Alabama with lessons from her grandmother whose herbal and healing knowledge had its roots in her Creek-Cherokee heritage.

Phyllis’ studies continued as an apprentice with the late Tommie Bass, a nationally renowned folk herbalist from Sand Rock, Alabama. She is the director of the Appalachian Center for Natural Health in Arab, Alabama, which offers both online classes and in-person classes. She’s also in the faculty of the Matthew Wood Institute of Herbalism. Phyllis is the author of Southern Folk Medicine: Healing Traditions from the Appalachian Fields and Forests, published by North Atlantic.

Welcome to the show, Phyllis.

Phyllis Light:

Thank you. Thank you for having me.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

Oh, it’s such an honor. I’m so excited to have you here. It’s been years since we’ve been together in person.

Phyllis Light:

Yes.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

I want to say it was the IHS and I don’t even remember which one, but it was a long time ago.

Phyllis Light:

It was a long time ago. Wait. Maybe it was at Bonnie up in the Midwest.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

No.

Phyllis Light:

No? IHS. Okay.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

IHS, yeah. I remember I got to go to the Teachers’ Lounge because I was a teacher. It was my first time there and so I was very excited. I remember hanging out with you and just thinking life is good. I’m hanging out with Phyllis Light right now.

Phyllis Light:

Hey, Teachers’ Lounge that’s a big milestone. I remember when I got into Teachers’ Lounge it’s just like, “Oh, my God! I made it!”

Rosalee de la Forêt:

And just randomly, another memory I have for that is I took one of your classes. I think it was on Southern folk herbalism. Somebody in the class asked you, “What do you do when you get the hangnail cuticle thing?” and you said, “The best thing to do is just put it down and stop playing with it.” I was like, “I love this woman.” It was just so practical. I was like, “Yeah.”

Phyllis Light:

That’s it. Leave it alone.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

We could continue to travel on the road of reminiscence, but I would love to hear your herbal story. I’ve actually heard it before and I love it, so I’m excited to hear-

Phyllis Light:

Okay.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

How you found yourself on this plant path.

Phyllis Light:

Alright. My father was a wildcrafter and herbalist, and so is my grandmother who was a midwife and herbalist back in her day, the Ruth Community and part of Cotaco Valley back in—but this was the ‘30s, ‘40s, that time period, ‘20s, ‘30s and ‘40s. Her mother had and her aunt had all been kind of midwives herbalists, so that too she learned from. It was just part of the family. I started in the woods helping when I was about 10 years old, learning to identify the plants. Not all the plants, but the plants that were needed, that we were harvesting for sale because that’s what a wildcrafter does, and part is harvest plants. Do sale because this was part of the living for the family.

That was my early beginnings. I went from there. I started seeing clients, I guess first time when I was about 19 because I’ve been with my grandmother or my dad or some family member learning since I was 10. It was like nine years. Now, did I have experience? Not a lot at 19, but back in that time period, I had been with grandmother and my family enough to—it was the same old thing over and over. Different world back in that time period. Nobody was on multiple medications. Nobody had health insurance. Nobody was overweight. Nobody was Type 2 diabetic, so it was acute things, digestive issues. Occasionally, some sort of reproductive issue, but rarely. I remember when I was about 23, I met my first person who had a prostate surgery ever for prostate cancer. It was a different health environment. Everybody grew their own food. Everybody was poor. There were no factories in town, no jobs. Everybody grew their food. It was just poor world Appalachian foothills. Everybody hunted or had a pig or chickens or a calf, that sort of thing. It wasn’t this sort of disorders I saw later or I see now. Let me put it that way--this world as I see now.

Anyway, this is where I got my early herbal training and then later, I studied with Tommie Bass who lived about an hour from me in the opposite direction, on a mountain in northeast Alabama. Tommie Bass had an amazing amount of experience. One year, when I was with him, we saw 3,000 people, if you can imagine.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

Wow.

Phyllis Light:

I know. I know.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

So, you just kind of shadowed him? Like he would see the people and you’d be there to support and apprentice?

Phyllis Light:

Yeah, yeah, totally. That was exactly it. He was a little bit different—approach from—my grandmother had been just very practical, very poor Southern-oriented. You make do with what you’ve got. They gather doing plants, that sort of thing. Now, Tommie also gathered all his own plant and he also sold plants to herb companies for a living. He did a lot of wildcrafting himself, but he saw a lot of people. A whole lot of people. Tommie’s clientele shifted because originally, it was more like my grandmother’s clientele of just the acute injury of, “Oh, my God. Oh, my God. The chainsaw slipped,” some of those injuries, acute things or I-fell-off-the-bluff-and-I-broke-my-arm kind of stuff. Originally, Tommie—this was Tommie’s clientele, and then somebody published an article in the New York Journal? No. New York some journal newspaper? Or some newspaper, and his name hit national airwaves, and all of a sudden, his clientele were people who could afford to pay, mostly college-educated. It just really shifted. It just really shifted.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

Do you remember when that was? About what year it was?

Phyllis Light:

I’m going to say that was probably with the New York Journal. I’m going to say that’s probably the late ‘80s or early ‘90s. Tommie died in ’96, so it was probably the mid until late ‘80s.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

Okay.

Phyllis Light:

At that point, he got upset because his whole approach had been, “Let me take you out in the woods. Let me show you the herb. Let me show you how to gather it. We’ll come back to the stow. I’ll show you how to cook it up. I’ll send you off with some and you go take care of yourself.” It was a very self-sufficient let-me-teach-you-how-to-fish approach. He almost quit. He got despondent because people would come and they did not want to go out in the woods. They did not want to know how to prepare it. They were like, “Just do this for me and I’ll pay you,” which is more like what’s going on now. “I just want the herb. I don’t want to be involved in any other part of it.” He got very despondent about it and thought about quitting for a while. Folks talked him into continuing and he did. He was really busy up until the year before he died. He died in 1996, so he was busy probably until 1995 and then the last year, he just didn’t feel well. He was 89 or 90.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

I’m curious. I could imagine why he was despondent and upset that people were just wanting to pay for it, but I’m wondering if you could put that more into words or what his philosophy was that made that so unappealing.

Phyllis Light:

He was very much of the generation of, “You should take care of yourself. You should know how to do these things. You are responsible for your health. Don’t try to make me responsible for your health. Let me show you how to take care of yourself. You are responsible for you.” That was kind of it in a nutshell.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

I can respect that and it is interesting the difference of today.

Phyllis Light:

Because now, I think we’ve floated more toward a pharmaceutical model whether we’ve realized it or not. “I want to just purchase my herbs,” which is fine. My view is, as long as you get them down your throat whatever. However you get them is totally up to you. I’m totally supportive of your process as long as you take them. I don’t care if it’s capsules or tinctures or teas or decoctions. Whatever as long as you take them.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

I hear the practicality of your maternal line coming through, which is very practical.

Phyllis Light:

Yes, it is. If they’re not taking them, if they come to see you and you go, “I’m only doing tinctures,” and they’re like, “I don’t like tinctures,” what have you accomplished? How have you helped them? Other than taking some money from them?

Rosalee de la Forêt:

What I find interesting is you had, I think, what so many of us yearn for--that ancestral lineage of being a plant person. It occurred to me that a lot of people have that dream for their children too if they’re herbalists now. Wishing their children would follow them, which I know that doesn’t always happen.

Phyllis Light:

No.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

So, you have this ancestral lineage of four generations, at least. You grew up within that and then you apprenticed with Tommie Bass. At what point—this is just personal curiosity—at what point did you find your herbal contemporaries like Rosemary or David Winston?

Phyllis Light:

In 1999, I went to work as the director of herbal studies at Clayton College. It’s really funny because I just saw David Winston and Matthew Wood this weekend and we were talking about, “What was your first herbal book?” My first herbal book was the Magic and Medicine of Plants by Reader’s Digest and I was like, “Oh, my God! A book about plants!” because my whole thing had been oral tradition. Everything I knew was oral tradition. I didn’t have another herbal book until I got a job at Clayton College, director of herbal studies. That was 1999 and I walked in and they said, “Here’s the library.” I looked and I’m like, “Holy…”expletive, expletive. There was a whole—there were bookcases and bookcases of herbal books. I had no idea they existed because I had just been down on my little mountain valley thing and did my own thing that whole time. I had no idea. What was my second herbal book? I don’t even remember. I just started devouring the books at the Clayton College.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

I think it’s such a unique experience because not a lot of people these days grow up in this—not insular, but you weren’t going to herbal conferences. You didn’t have a large herbal bookshelf because it didn’t exist back then even.

Phyllis Light:

There was no internet. It was Matthew Wood when I went to work at Clayton College. It turned out Matthew Wood had been doing some consulting with the college in the herbal program. We met over the telephone around 2000. Matthew was the person at the next IHS I went. We actually met in person there. I don’t remember what year that was. It had been 2000 or 20001, somewhere in there. He’s the person that introduced me to the broader herbal community.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

What I think is interesting about that, Phyllis, is that if we grew up with a lot of influences then there can be a lot of repetition naturally. I feel like reading your book and taking classes with you, you have just an interesting perspective that you don’t hear repeated throughout a lot of people because you have this unique herbal upbringing. I just think that’s a gift that you bring and perspectives that you bring that I find really valuable.

Phyllis Light:

Thank you. Thank you.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

Thanks for sharing for your story and answering my personal curiosities there. I appreciate that.

Phyllis Light:

Yeah.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

Do you have anything else to add? Or should we jump into-

Phyllis Light:

I was just going to say in this time period, I thought it was very important to expand and so, I have also worked in mental health. Even before I was at Clayton College, my first foray was into mental health. I was a physician’s assistant in mental health at a county mental health center. If anybody has ever worked at a county mental health center, you know what that means and who your clientele is. I also worked at a drug rehab center associated with the county mental health center. Later, I got my master’s degree from the University of Alabama in nutrition and healthcare because I think nutrition is also important. I’ve worked in doctors’ offices and I really support having tradition, but having some science too. It’s a different world. When my average client comes in with six different medications, I need to know a little bit more than my grandmother did in that situation of herb-drug reactions and physiology. So, I encourage everybody to continue their education.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

Thank you, Phyllis. You’ve chosen a plant for today that’s never been on the show before and one that I intuitively love, but I haven’t really worked with much beyond flavor, really.

Phyllis Light:

Okay.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

So, I’m excited to hear what sumac is good for with you. I wonder if the first thing we should discuss though because there’s probably somebody out there wondering why we might be discussing a toxic plant. It always comes up.

Phyllis Light:

Okay. So, sumac, there are four or five different species of sumac. It depends on where you live. Only one of them is toxic. The rest are medicinal or edible or both. The toxic plant is actually quite easy to determine from the others. All the other species—the medicinal species have red to rust, to brown berries. The poisonous sumac has green to white berries and they never change to any other color. They’re very striking. These white berries that stick up above the green leaves is very striking, but you see that, don’t even touch it because some people actually get a little rash from touching it. So, caution there. There are the other species that are not toxic, highly medicinal, have, like I say, red to rust, to brownish red berries. In my area of the woods, we have smooth, winged. We have the poison, but we’re going to forget about that for right now. We have a little bit of staghorn and a little too far south for a lot staghorn. There’s one called “fragrant sumac” that is found more out west along with some of these other ones, and it is medicinal also. It has a pinkish lavender red berries. It’s a little bit different. Anyway, poisonous sumac needs a lot of moisture. The other sumacs don’t need as much moisture. It really likes a swampy land or land that has moisture. Again, remember the white berries. Now, we’re going to forget about it. Always, if you’re looking to identify a plant, have your book with you if you don’t know it or ask someone who’s smarter than you on that.

Staghorn is probably the most popular, further north from me. It gets to a height of about 12 feet. The berry clusters stick straight up like a staghorn. I have the smooth, which tends to have almost mauve berries, mauvish red berries. It also sticks up, but it has a little curve on the end. My favorite is winged and we have a lot of winged. Winged sumac on the stems of the plant coming off the branches has a little extra leaf material on the side of the stems before it goes into the stem. Winged sumac is spread out like a hand. All the rest of them are like this. Winged sumac is like this. It gets maybe 10 feet tall. This is a big year for sumac. I’ve been seeing sumac everywhere. I’ve been seeing fields of elderberry flowers, it’s unreal how much elderberry there is this year. In Southern folk medicine, when you see a plant that’s in abundance that means gather it because you’re going to need it in the time period coming up. So, I will be gathering elderberry and I will be gathering sumac this year.

The berries are covered with these tiny, tiny little hairs that fall off when they dry. I just dry a whole head. I don’t take all the berries off the head. I just dry the whole head. Sumac is unusual in that it never feels totally dry and you don’t want it to. If it gets too dry, then it’s coated in malic acid in an oil. If it gets too dry, it has lost its medicinal activity. I have sumac that I’ve had for five years. Every time I use it, I feel of the berry. If it feels tacky under my fingers, I know it’s still medicinally active. When it feels dry, it’s time for me to throw it out. It’s not working anymore. It doesn’t need any—I keep mine in a brown paper bag. It doesn’t need any kind of special storage. Somebody might want to freeze it, but when the dried is lasting five years, hey, it’s time to get new anyway. I dry on my kitchen counter maybe three to five days. Again, you don’t want it to get too dry. You want to keep the tackiness. I just throw it in a brown paper bag. I’ll stuff it back on the shelf, close the door. When I need it, I’ll just pull out, cut off a head of sumac and bring it out. Keep that in mind.

If after the weather turns cool if you go out to harvest and the berry heads have turned like this, you’ve missed your opportunity to harvest because when they’re no longer medicinally active or the weather gets too chilly or the frost hits, they droop. They’ll start turning brown and when they droop, they’ve lost their medicinal activity. Every single part of the sumac plant is medicinally active. I use the berries because they taste good. They have that little extra bit of malic acid and I’m not damaging the plant. Sometimes I get the leaves, which are a lot more tannic than the berries. The berries are easy to get. They taste good. No tree damage. My mother called this plant “shoemaker” because back in a certain time period of her life, they used the root to make soles of shoes. They use the wood also sometimes to make gunstocks. It’s a dense wood, but it’s kind of soft at the same time. It’s dense, but soft. It was used—it’s not a timber. Remember it’s only getting about 12 feet tall and it’s really like a big shrub. At least, where I’m at.

Anyway, that’s the background on sumac. Leaves, stem, root, bark, seed heads – all are medicinally active. My favorite, of course, is drying it too, but I’m a folk medicine tincture. To make a tincture, I just stuff a bunch of seed heads in a jar and pour in some alcohol. I’m done. I know it’s not everybody’s method of medicine making, but it works really good and you’ll have a really lovely red tincture.

If you’re making a decoction out of it, a seed head and about three quarters or a quart of water is what I usually use. Southern decoctions are brought to a boil and then taken down to a simmer for about 10 minutes and then turned off. Let it sit, no top on it. There’s no lid on the pot and I’ll let it sit. It will also be a lovely red to maroon color. It will have a bit of a sour taste because the berries are sour. The more leaves you have in it, the more bitter it’s going to be. Now, you can say that the—but if you cook the berries. If you boiled them or simmer them for 20 minutes, now you’re going to have bitter in your decoction. It’s sour underlying that bitter taste on sumac, which if you’re into taste gives you a little bit of medicinal activity. The leaves were boiled or can be boiled and used as a topical fungus remedy.

Is it better than black walnut for fungus on the skin? It’s just a little bit different and sometimes I mix sumac decoction with black walnut decoction to get rid of ringworm, yeast on the skin, fungus on the feet--very useful for doing that. Skin rashes, skin ulcers. Really good applied externally for hemorrhoids, and also, the tea can be drank also to help shrink up hemorrhoids.

The decoction is really good for sore throat if you want to make a little gargle. Gargle it back down there. Really useful for sore throat, any kind of those canker sores. If you have a canker sore, just rinse with sumac a couple of times a day and pretty soon they’re gone, let me tell you, pretty quick. It tightens up the gums. Good for teeth and gum problems.

The winged I use because it looks so airy compared to the other ones. I use the winged for respiratory issues. I use quite a bit of it back during COVID. It helps make a productive cough. It helps tone mucous membrane tissues regardless of whether its lungs or gut or bladder. It is—“indicated” is the word I’m looking for. It’s indicated with any kind of UTI, kidney disorder, bladder issue. It’s very toning on the bladder, diuretic without being exhausting on the kidneys or irritating on the kidneys. Maybe that’s a way to put it. So, traditionally used for kidney infections, bladder infections, anemia, and this is where it’s got my claim to fame. As far as what I want to use it for most often is going to be anemia related to poorly functioning kidneys, but it can be useful for any kind of anemia. The kidneys make a hormone called “erythropoietin”—I think is the name of it—which signals the bone marrow to make red blood cells.

When people have kidney disease, pretty soon they’re anemic. As an example, one time I had a client who was maybe 28 or 29. She was on dialysis three times a week. Her kidneys had been damaged because she had taken over her young lifetime so much Tylenol and ibuprofen that it had actually killed her kidneys pretty much. I taught her how to cook up sumac at home and asked her to drink a cup or two a day, whatever her tummy like. She actually—it was interesting because every time she came to see me, she would bring the blood work from her dialysis so we could see what was changing and what wasn’t changing. She said this was the first time she had never been anemic with dialysis, and that is pretty huge if you think about it. It’s pretty, pretty darn huge. The doctors were like, “This must be wrong. You’ve got to be anemic. Everybody’s anemic because that is the nature of dialysis,” but as long as she drank the sumac, she had more energy and she wasn’t anemic.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

Wow.

Phyllis Light:

It was pretty awesome. Pretty, pretty awesome.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

I feel like there’s a lot more people who need to know about that.

Phyllis Light:

Yes. Sumac tea leaves--you can use leaves of berry. Anti-diabetic, it will lower blood sugar, and it was one of the traditional, along with huckleberry leaves for diabetes in my grandmother’s day. It is still the main thing I go for for lowering blood sugar. At the same time, it is antibacterial, antiviral. James Duke when he was investigating various plants, he’s got Duke’s database or he had Duke’s database. He said that sumac tested against more organisms than any other plant he had tested--more than Echinacea, more than elderberry. It had more anti-infective, antiviral activity, he thought, than those two plants. He was like, “I don’t know why people aren’t using it anymore. Why aren’t they using it more often?”

Rosalee de la Forêt:

That’s exactly what I’m thinking in my own head right now. Why am I not using this plant more often? I’m so inspired. This is so amazing.

Phyllis Light:

I think it’s because nobody really knows about it. I’ll keep it and I use it literally all the time. There’s probably not a week or two goes by I’m not recommending it or not using it for something. It can be the decoction can be made into a wash for bedsores and ulcers on the skin. It helps wash out bacteria and dry up the open ulcers and wounds, which then allows healing to take place. It’s a poison ivy wash, so it will help—this is after you have poison ivy and you know you have poison ivy. It will help strip the oils off with the decoction, which is again bringing it to a boil for at least five to ten minutes. No, no, I’m sorry. Bring it to a boil. When it gets to a boil, turn it to a simmer for at least five to ten minutes, and then just turn it off and let it sit. Really get the poison ivy wash. I use that. Sometimes I put some plantain in with it because I simply work really well together for poison ivy. Those are good. Bleeding ulcer--it stops the bleeding internally and externally, which is why it was really useful for wounds and hemorrhoids. It’s also good for bleeding ulcers. That’s maybe not going to heal the ulcer up completely, but it will stop the immediate bleeding. It can stop bleeding from ulcerative colitis. Very useful plant.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

Yeah.

Phyllis Light:

If you break a twig on a sumac plant, there’s a little black milk. We call that “latex” or “milk sap.” We call it milk sap. Latex can be used topically or was used topically for sunspots, skin spots, moles. It has the activity other latex-bearing plants do to eat away things on the skin. It was there. It can be smoked. The dried leaves can be smoked to open the lungs. It was considered as asthma remedy. I’ve only done that a couple of times and I’m like, “Oh, my God! This is so harsh!” So terribly harsh that you start coughing and whatever is in there, you cough up and you’re better just because it has done that. I find most smoking blends a little too harsh. That’s just me and my lungs.

Sumac lemonade is what it’s called. It’s a nice little summer cooling beverage. In the old vernacular, sumac was considered cooling and a refrigerant. Sumac lemonade easy to make, just throw a head or two. It depends on how much you want to make. Say, you want to make a gallon of it, throw about five heads into the pot of water. Just bring it to a boil then let it sit until that water gets really red. It also makes a really good sun tea, which I’ve actually done more often than the stovetop method. It’s where I stuff a bunch of heads into a gallon of water. Remember I’m in Alabama. It gets pretty hot in the summer. Top on it, put it out in the sun and you can just watch the water change color over time. Three or four hours later, you have this amazing beverage and you haven’t heated up your kitchen. Some people like it sweetened and some people just like it as is. It’s not as sharp as a lemon, for sure. It’s definitely sour, but definitely cooling. So, either one. I have actually found sugar is a little bit nicer sweetener with it than honey, but your choice. Honey when it’s hot is a little cooling. It gets hot here. It may not be the same where you are.

Super useful for cough, colds and flus of any kind. I mentioned lungs. I had used it for COVID. Sinus infections, your odd virus that are RSV or whatever happens to be going around, it really does help dry all this up without suppressing the activity of the lungs. If it needs to move, it will still move. It’s not suppressing it that much, but it does help dry up a little the excess nasal. One time, we had one of these things going through my house. It was horrible. If you turned your head down, mucus would come out your nose. It was copious mucus. I looked up at my daughter who was coming through the house. She had taken toilet paper, twisted it and stuck that both her nostrils. It was so funny.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

So miserable.

Phyllis Light:

Yes. I was like, “It’s time for a sumac,” so we go make some sumac. I didn’t realize it was that bad. Just in that short time, it dried it up. It works well with peppermint or spearmint and it tastes really good to help dry up sinus congestion. If you have a sun tea, it’s going to be also high in Vitamin C. If you cook it on your stovetop, less Vitamin C. Because it’s a diuretic and it’s supportive of the kidneys, it can help lower blood pressure. I would say almost as good as a prescription diuretic without the side effects that go along with it. Last, but not least, as far as medicinal activity goes, they help reduce fever because it is cooling. You need herb that’s cooling enough that’s going to help lower fever, but it can do it very pleasantly with a good taste. This is it.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

Is that all? I’m just kidding. I’m seriously just wondering how is this herb so understated? Why have I not worked with it more? I’m just mind blown right now.

Phyllis Light:

I don’t know. It’s all good. Very popular here in the Deep South, but I don’t think it just made its way out into the world. Into the herbal world, I should say.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

Previous to this, I’ve heard of sumac lemonade. It’s often in za'atar blends.

Phyllis Light:

Yes, yeah it’s in za’atar blends.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

That’s how I’m familiar with it, but I’ve never worked with it medicinally. Wow! I’m excited. There’s nothing like finding a new plant to work with.

Phyllis Light:

Right.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

Renewed inspiration and joy.

Phyllis Light:

I think you’ll like it. I think you’ll like working with it.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

When I saw your recipe that you’re sharing with us, it’s this blend of sumac and elderberry. I’ll let you describe it, but I didn’t know much about sumac. I was like, “That’s an interesting combination,” but now, because of what you shared, I think I get it. Would you like to talk a little bit about the recipe?

Phyllis Light:

It’s an equal amount of sumac and elderberry. I’ll briefly go over how to make it here in a second. I find the elderberry a little cloying, a little musky cloying taste. Sumac is real crisp and sour. It really cuts the cloyingness of the elderberry. They have some similar activities and overlaps, but sumac is a little bit stronger—and I’ll stand behind that statement—than elderberry. It just hasn’t been researched in the same way that elderberry has, but traditionally, traditional herbalists in the South, elderberry or sumac, they’re like, “Elderberry, no. Sumac. Elderberry. Sumac.” I’m going to take sumac.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

I feel like if you were in a room of herbalists, Phyllis, and you stood up and said, “Sumac is a little bit stronger than elderberry,” I feel like that could be a really fun thing to watch unfold.

Phyllis Light:

I will be crucified. I will be totally crucified, but that also tells me they’ve never worked with it.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

Yeah.

Phyllis Light:

They have never worked with it, so they don’t really know. Sumac elderberry syrup is what I would make every year for my kids--for me and my kids for the winter. Some people like jelly, but I think the syrup has more potential ways to use it. During cough, cold and flu season, I will be like, “Let’s have this on our pancakes.” It’s an immediate, handy cough syrup. “Alright. Let me get a cough syrup,” and it just tastes so good. The two together tastes so much better than—it just taste wonderful. Or I would go, “I got some fizzy water. Let me put some of this in the water and we can have this.” When we were at herb school, we put it on our ice cream. We also made homemade ice cream and then we had elderberry sumac syrup to go on top of our homemade ice cream. There’s just much more things you can use it with. It cans really easy. I never water bath can it, my personal preference. I know technically, if you’re doing a jam or jelly, you should put it in a water bath for 10 minutes, but this was so sour and has so much acid, I didn’t personally feel like I needed to. I also knew we’re going to go through the whole thing in a year, so not a big deal. Five years later, I would open it. I’d find one in the back of the cupboard and we’re like, “Yay!” and it would still be fine.

Basically, I would say a head or two of sumac. The recipe actually kind of measured for you all that goes along with this. A head or two of sumac, a big can full of elderberry. These are my normal measurements. I had to think about putting it in cups. Forgive me if the recipe measurements aren’t quite right.

Anyway, big, thick handful of elderberries, a couple of heads of sumac and if they are small heads, make it three. About a quart of water or a quart and a half of water, bring it all to a boil. Simmer it for about 15 minutes. Turn it off and let it cool enough to work with it and then strain all that out. Measure it and let’s say you end up with a quart of decoctions, so now you’ve got this really good decoction. You’ve got a quart, which is 2 pints, which is how many cups? Anybody know? I see the wheels turning. So, there are two cups to a pint, right? You have two cups to a pint and you’ve got two pints in a quart, so that’s going to be four cups of sugar, and please use sugar for it to seal appropriately. To make sure it seals is another cup of sugar, so you’re going to end up with five cups of sugar. You may go, “That’s five cups of sugar!” Yeah, but you want it to seal. You want it to preserve and sugar is a preservative. That’s why it’s in there. Honey if you decide “I really want to use honey.” Just be aware you’re cooking it and you’re going to lose a lot of the effects of honey and sometimes honey doesn’t seal quite as well as sugar does. There was a reason traditionally use sugar as a preservative. You also squeeze the juice of half of lemon into all this.

You’ve got all this back in a pot. You’re stirring it up. You bring that to a boil. The color of the sumac is red. The color of the elderberries is purple. Your syrup is going to be fuchsia. It is the brightest. I made it for Rosemary was down visiting once and I shared some with her and she was looking at the color. She started laughing and she said, “This is the hottest. This is hot. This is like passion.” She said, “This is like passion in a jar.” That’s the color of it. You are like, “Wow! Where did this color come from?” The lemon juice really brings it out. It brings the color change out.

If you want to can it, now you’ve got some hot jars going over here on the side. You boiled your jars. They’re sterilized. You keep them hot. You have your rings. You have your taps. You’ve got them in another pot. You’re keeping them hot. The sumac has boiled up and elderberry is boiled up really good. You’ve got it on a low simmer because it has to go into the hot jars hot with the hot taps and the hot rings for everything to seal. And there you have it. I try to can. In a good year, the last four years, there hasn’t been a lot of sumac, so I’m very hopeful I’m seeing a lot this year that I’ll be able to gather some.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

I love that you said sumac and elderberry are big this year.

Phyllis Light:

They are.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

Your combination is the year for it.

Phyllis Light:

It’s the year for it. It’s the absolute year for it, so I’m very excited about that because I have been out—I finished mine out during COVID and there just wasn’t any sumac. By the time I would get to it, bugs or something would get to it.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

Interesting.

Phyllis Light:

You have sumac lemonade, sumac syrup, sumac decoctions and sumac tinctures, so many ways to preserve it and to use it.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

Including over ice cream. You’ve really covered a lot of bases here.

Phyllis Light:

I did. It is your medicinal food. Hot butter biscuit. Endless food uses for this.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

Thank you for sharing so many of those. For the sumac elderberry recipe in particular, everyone can download this beautiful recipe above this transcript. Thank you, Phyllis.

Phyllis Light:

You’re welcome.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

Thanks so much for sharing about sumac. I’m genuinely super excited to start working with this plant. I know we have sumac in the area. I’ve looked at it with curiosity. I just haven’t taken that next step and now I feel much more empowered to do so, so thank you.

Phyllis Light:

Good, good. You’re welcome.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

Next, I would love to hear what kind of herbal projects you have going on.

Phyllis Light:

Okay. I have an herb school, so I’m still teaching. I get around the conferences. I’m working on the second Southern Folk Medicine book to write about the things like high blood, low blood, the blood types that I didn’t cover in the first book. I’m working on that. I have grandkids now. That’s a big herbal project. “Hey, we’ll spoil the dandelion,” fun things with grandkids. That’s what I’m doing. I teach other herb schools on occasion, stuff like that, and just really see clients. I still see clients and just stay busy. I stay herbally busy.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

What’s the best place for people to find you, Phyllis?

Phyllis Light:

Just go to my website. Just my name, phyllisdlight.com. Go to my website, hit “Contact” and I will get back with you for sure.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

Wonderful. Thank you so much for all of this. Before I let you go, I have one more question.

Phyllis Light:

Sure.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

The final question for you is one of my favorite questions and that is, how do herbs instill hope in you?

Phyllis Light:

That’s actually more complicated question than—or less simple question than it first seems. It’s a pretty deep question when you think about it. I would say it’s not just hope although there is hope there, but also continuance, survival. When I think about the world and the environment, when I think of what we’re doing to the earth and how many species we’re losing in some part of the world every single day, it then becomes—okay, hold on. Let me get ready here. I can’t talk without my hands. It becomes really important for us to think about conservation and ways to make sure we’re not going to lose our plants, and ways to make sure traditional uses or plants are not lost.

We have this thing with the internet of, “I’ve done this, you all try it.” I will Google “herbs for Type 2 diabetes.” Seven or eight or nine herbs come up. Then I’ll Google “herbs for autoimmune disease,” the same seven herbs will come up. I’ll Google “herbs for colds and viruses,” we got four or five of the same herbs coming up. So, there’s this thing that’s happening in the world, in the healing communities and the herbalism of we’re limiting the plants that we’re using. We’re limiting our knowledge of the plant and it’s much more also pharmaceutical approach.

I just talked about sumac, which was so common in my early training and how many people are using sumac out there? Look at all the uses. It’s not on that list of seven herbs. One of my hopes is that we can move or see past this internet craze and we find our knowledgeable teachers and our knowledgeable books away from the—I call it the “fast 10 herbs on the internet”–and that we move into saving that information, but we’re also moving into saving the plants also at the same time. I have a hope that the plants themselves will show the way, so to speak. The more we use them, the stronger they get. The more we spread that information, the more likely we’re going to save the plant. That is one of my hopes.

I know this is maybe the reverse of what you were talking about when you first asked the question, “How do plants give me hope?” I’m actually trying to give the plants hope. I actually want to go in the other direction. So, they’re not dying off. So, they’re not being killed off. They were here first. We came last. Regardless of what system you want to look at, we came last. I want to somehow acknowledge and thank them for all their uses and that they are there for us, but also want to work hard that they’re not diminished or devastated or eliminated in any way possible. Whatever I can do to help make that happen that’s what I work on.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

I can tell you’re doing it. Here you are, sharing sumac and spreading the word. I’m know I’m not going to be the only one who’s inspired about this plant. I really like what you said, Phyllis, about this kind of thing that’s happening right now where our herbal materia medica is becoming condensed. In some ways, I think it’s good in that the popular mass-produced herbs can be the ones that are the most ubiquitous, but on the other hand, we can’t lose this knowledge.

Phyllis Light:

Yes. We can’t. I just think about how much plant knowledge is not being used from, let’s say, the medieval period. They used to haul up more plants than we do. The information, many times is still there in old herbal books, but then we read the old herbal books and we think, “Can you really use elecampane like that?” We start to question it, but here’s a practitioner who, let’s say, used elecampane for digestive difficulties where we only think about it as a lung herb for coughs, colds and flu. It was a #1 pinworm remedy for little kids. Huge digestive plant. Even with the plants that we are familiar with, we are losing or forgetting some of their many, many uses because plants are full of secondary metabolites and phytochemicals. One plant can do many, many, many different things, so we shouldn’t pigeonhole them either.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

That’s so much about what this podcast is about, and you have been a most excellent guest. I’m so deeply appreciative. I feel so deeply appreciative of sumac and I can’t wait to work with it. What you just said makes me think of just how important it is to spend time with one plant. Not just memorizing facts about a plant, but to really work with the plant with different people, different ailments, and really see the possibilities there and to get away from fast herbalism.

Phyllis Light:

Absolutely. Yeah, totally, fast food herbalism, that’s what we got.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

Thank you again so much. Thanks for being here and thanks for sharing so much wisdom with us.

Phyllis Light:

Thank you for having me. Bye.

Rosalee de la Forêt:

As always, thanks for being here. Don’t forget to download your beautifully illustrated recipe card above the transcript of this show. Also sign up for my weekly newsletter below, which is the best way to stay in touch with me. You can find more from Phyllis at phyllisdlight.com.

Tired of herbal overwhelm?

I got you!

I’ll send you clear, trusted tips and recipes—right to your inbox each week.

I look forward to welcoming you to our herbal community! Know that your information is safely hidden behind a patch of stinging nettle. I never sell your information and you can easily unsubscribe at any time.

If you’d like more herbal episodes to come your way, then one of the

best ways to support this podcast is by subscribing on YouTube or your

favorite podcast app.

I deeply believe that this world needs more herbalists and plant-centered folks and I’m so glad that you’re here as part of this herbal community. Also, a big round of thanks to the people all over the world who make this podcast happen week to week:

Nicole Paull is the Project Manager who

oversees the whole operation from guest outreach, to writing show notes,

to actually uploading each episode and so many other things I don’t

even know. She really holds this whole thing together. Francesca is our

fabulous video and audio editor. She not only makes listening more

pleasant. She also adds beauty to the YouTube videos with plant images

and video overlays. Tatiana Rusakova is the botanical illustrator who

creates gorgeous plant and recipe illustrations for us. I love them. I

know that you do too. Kristy edits the recipe cards and then Jenny

creates them, as well as the thumbnail images for YouTube. Alex is our

tech support and Social Media Manager, and Karin and Emily are our

Student Services Coordinators and Community Support. For those of you

who like to read along, Jennifer is who creates the transcripts for us

each week. Xavier, my handsome French husband, is the cameraman and

website IT guy. It takes an herbal village to make it all happen

including you.

One of my favorite things about this

podcast is hearing from you. I read every comment that comes in and I

share really sweet ones with the guests. I’m excited to hear your herbal

thoughts on sumac.

Okay. You have lasted to the very end of the show which means you get a gold star and this herbal tidbit:

Okay,

so wow! I had no idea about sumac’s many gifts and potential. I feel

like it’s an herb that’s just been on the periphery for far too long, so

I was really excited to hear more about this plant from Phyllis and I’m

really excited to work with this plant myself.

So,

right after interviewing Phyllis, I went to PubMed because I just

wanted to see out of curiosity what studies and research there’s been

done on sumac, and there’s a lot! Especially, in regards to lowering

blood glucose, modulating inflammation, reducing high blood pressure and

balancing cholesterol levels, which if you know me at all, is the stuff

that I often like to talk about, so I’m excited to get to know this

plant better.

There was also a randomized clinical

trial that showed that a sumac and rose mouthwash had better results

than a pharmaceutical for reducing radiation-induced oral mucositis. It

also improved the quality of life in patients with head and neck cancer.

So, that’s really cool and powerful stuff there, and I love that

combination of sumac and rose. I’ll include a citation for

that study below.

Again, I look forward to hearing your thoughts on sumac.

Citations for What is Sumac Good for:

Ameri, Ahmad, et al. “Sumac-Rose Water Mouthwash versus Benzydamine to Prevent Radiation-Induced Oral Mucositis in Head and Neck Cancers: A Phase II Randomized Trial.” Journal of Cancer Research and Clinical Oncology, vol. 149, no. 10, Aug. 2023, pp. 7427–39. PubMed, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00432-023-04687-1.

Rosalee is an herbalist and author of the bestselling book Alchemy of Herbs: Transform Everyday Ingredients Into Foods & Remedies That Healand co-author of the bestselling book Wild Remedies: How to Forage Healing Foods and Craft Your Own Herbal Medicine. She's a registered herbalist with the American Herbalist Guild and has taught thousands of students through her online courses. Read about how Rosalee went from having a terminal illness to being a bestselling author in her full story here.